Evaluation of Pharma-Sponsored Patient Support Programs (PSPs): Why Assessment Is Often the Forgotten Piece of the PSP Lifecycle Jigsaw

Jessica Walburn, PhD; Clare Moloney, PsyD, IQVIA, Reading, UK

The Challenge and Why It Matters

The purpose of a patient support program (PSP) is to improve the lives of patients by supporting adherence to treatment and self-management of chronic conditions. However, pharmaceutical companies that provide these programs often don’t know whether their programs are achieving their objectives. To date, comprehensive measurement of industry-sponsored PSPs is rare, holding back our understanding and curtailing empirically based improvements in program design and opportunities to enhance impact.

Health psychologists and implementation scientists working in the pharmaceutical industry are starting to apply theories, methods, and processes commonly used in public health or academic settings to patient strategy.1 This has facilitated a greater understanding of the way people behave and cope with a chronic condition. More importantly, their systematic application of theory to identify modifiable determinants of behavior has enabled the selection of evidenced-based behavior change techniques for use in PSPs. Behavioral scientists strive to adhere to guidelines for complex intervention development2 while recognizing the need to be flexible and practical. These insight- and evidence-based interventions provide the foundation for the PSP design translated into the program by a wider team of professionals, including content experts, engagement specialists, and graphic designers.

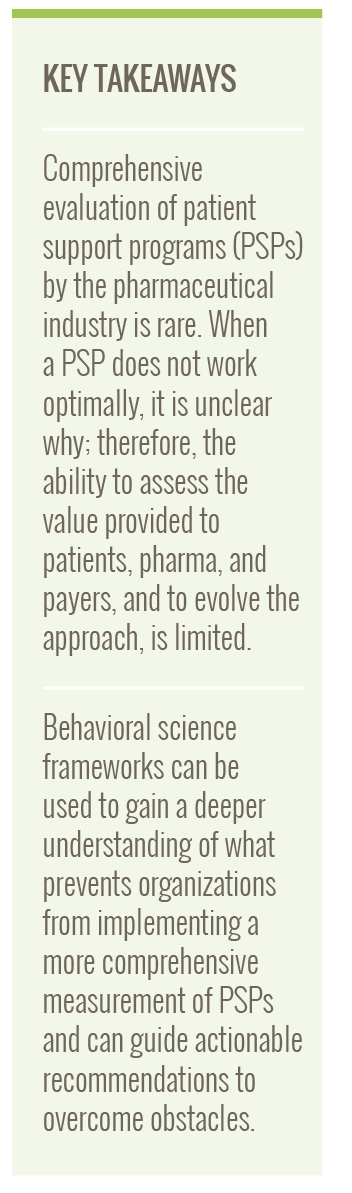

We consider that 3 types of data should be gathered as part of routine service evaluation:

- Operational data that tell us whether the PSP is running as intended (eg, number of enrollments, time from consent to first contact from PSP staff).

- Perceptions and experiences of those receiving the program.

- Data related to the key behavioral outcomes that the program is designed to encourage (eg, treatment adherence, perceptions about condition and treatment).

Data types can be combined to provide a comprehensive understanding of different dimensions of impact. For example, satisfaction with a program can be assessed by self-report questionnaires and operational metrics (eg, numbers of users leaving the PSP early). Improvement in behavioral outcomes can be assessed using a within-participants approach by measuring change over time from enrolment to an appropriate follow-up timepoint.

Without looking inside the black box of the patient support program, it is more difficult to refine and evolve programs or learn from success and mistakes. Furthermore, without real-world data, it is impossible to demonstrate value and impact.

Building on this routine evaluation, exploring a wider range of clinical and disease-related outcomes is also possible through the setup of protocolized research. Currently, PSP evaluation frequently stops at gathering of operational metrics and the extent to which participants would recommend the program to others. This leaves many unanswered questions:

- Is the PSP changing the behavior it was designed to target?

- Is it changing beliefs about treatment and disease?

- Is it improving knowledge?

- Is it building confidence to self-administer treatment?

- Which program asset is most/least effective?

- Are participants engaged and enjoying participation?

Without looking inside the black box of the PSP, it is more difficult to refine and evolve programs or learn from success and mistakes. Furthermore, without real-world data, it is impossible to demonstrate value and impact.

Figure 1. Three data categories recommended for robust PSP service evaluation

Applying Behavioral Science Change Theory to Understand Factors Contributing to the “Failure to Measure” Phenomenon and Guide Actionable Recommendations

To systematically investigate the barriers to PSP evaluation by the pharmaceutical industry, we applied the Capability Opportunity and Motivation-Behavior (COM-B)3 framework. We used a practical mixed-methods approach to analyze the perspectives of 23 representatives from international pharmaceutical organizations. The attendees were a self-selected sample of employees from different roles, with varied experience of PSPs, who decided to attend a workshop on PSP evaluation. These perspectives were gathered during workshop group activities. We wanted to build a “bottom-up” understanding of the barriers of evaluation and elicit the perspectives of attendees by facilitating whole-group discussions and small group work. We encouraged discussions to flow naturally, only prompting when conversation stalled. In real time, we classified the barriers described using the COM-B3 framework and assessed perceptions about evaluation in a short questionnaire.

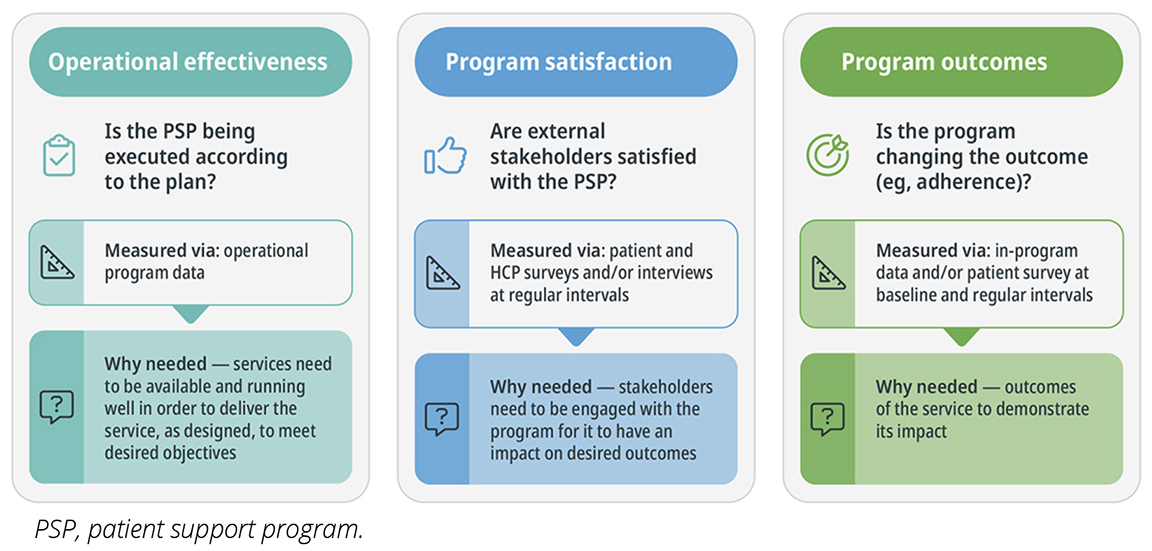

COM-B 101

According to the COM-B, a behavior is more likely to occur if an individual has the capability to carry out or “do” the behavior, is motivated, and has the opportunity to successfully enact the behavior. Capability factors include physical and psychological capacity, such as knowledge and skills. Motivation has a wider meaning than its everyday parlance, including all the conscious cognitive brain processes that underpin intention, such as beliefs about the behavior and beliefs about one’s capabilities or skills, as well as unconscious phenomena such as routines, habits, and emotions. Opportunity factors include anything outside of the person that can enhance or diminish the likelihood of a behavior happening. This includes things like access to resources, tools, and relationships or support from others. In a COM-B perspective of the aim to increase physical activity, the person needs to have the knowledge and physical capacity, think activity is worthwhile and likely to achieve benefits, have positive emotional responses and daily routines that increase their chances of success, have access to facilities, and have people around to support by encouraging or joining them in the activity.

Figure 2. Visual of COM-B

Findings

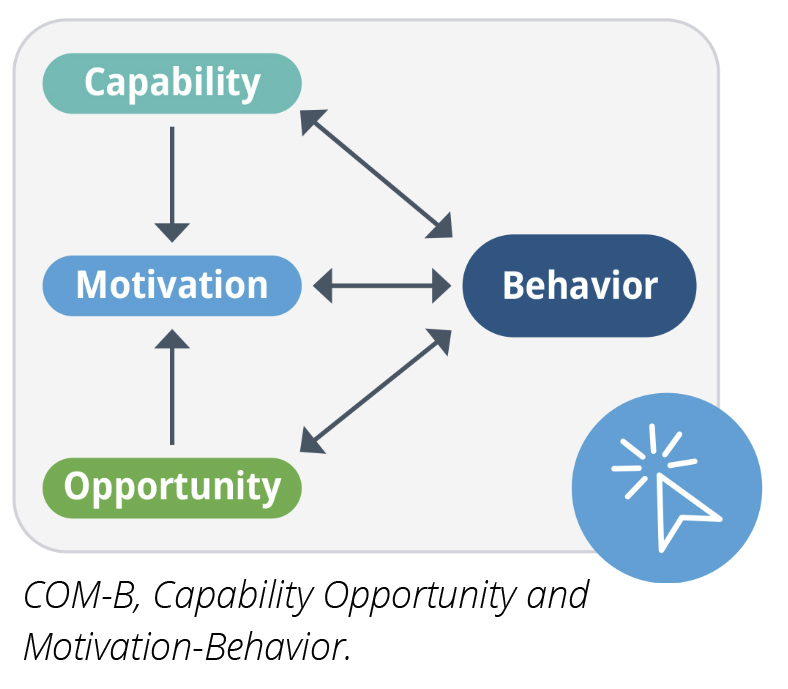

While all attendees recognized the importance of evaluation, the majority (82%) felt they lacked the necessary skills to implement a best-practice approach. Multiple barriers from each COM-B category were described that, at first glance, appeared daunting; however, upon closer inspection, the barriers included those that are more amenable to change.

Robust evaluation is a critical piece in the jigsaw of effective patient-centric service delivery.

Attendees lacked knowledge about regulation and infrastructure needed for data collection. Key motivational barriers to implementing a more thorough evaluation protocol included fears related to the consequences of how PSP metrics would be received both internally and externally, uncertainty about how to address any issues identified, reluctance to increase participant burden by requiring additional surveys, and concerns about sharing intellectual property if data were published. Opportunity barriers were significant and included low priority within organizations, frequent shifting of internal initiatives resulting in stopping of funding streams, and movement of staff, stalling momentum.

The application of the COM-B improved understanding of the evaluation barriers faced by those in charge of patient services within pharma, and, more importantly, guided the identification of actionable opportunities to drive change. COM-B is linked to a more detailed framework of domains associated with behavior change (The Theoretical Domains Framework)4 and a taxonomy of evidenced-based behavior change techniques.5 We used these to select effective interventions tailored to the barrier type. These recommendations include:

- Provision of tailored information to fill knowledge gaps.

- Training to address fears and misconceptions using case examples and peer experiences.

- Guidance to patient service teams encouraging cross-functional collaboration to develop measurement frameworks.

To address a number of the key barriers, we conducted a pragmatic review of pharma-sponsored PSPs published in peer-reviewed journals6 and summarized our findings in a factsheet, shared with workshop attendees. The factsheet aimed to address capability barriers by demonstrating what can and has been done, motivational barriers through demonstration of positive outcomes, and opportunity barriers by demonstrating the feasibility of PSP evaluation.

Figure 3. Categorization of Key Barriers and Interventions Classified by COM-B

Lessons Learned and a Call to Action

Robust PSP evaluation is a critical piece in the jigsaw of effective patient-centric service delivery. Future PSPs are unlikely to benefit from the insights provided by Implementation Science7 if real-world data are not available to assess how PSPs work in practice. Without it, PSP developers and behavioral scientists are designing at a disadvantage because they must make decisions based on anecdotal experience rather than an empirical evidence base. This analysis uncovered real challenges to PSP evaluation from the perspective of the pharmaceutical industry. Some require significant shifts in organizational structures, while others can be tackled bottom-up with small initiatives that can start to shift the needle. Evaluation strategies that assess program execution, satisfaction with services, and change in behavioral outcomes will provide the data needed to drive ongoing service improvement. Overcoming the barriers that hinder evaluation of PSPs will help patients experience the full benefit of their prescribed treatment (eg, better adherence and self-management) so pharmaceutical companies can maximize the improvement of patient outcomes from the medicines they develop.

References

- Riaz S. Patient Engagement in Pharma: A Psychologist Perspective. London: Springer; 2024.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behavior change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behavior change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behavior change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12:77. doi:10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81-95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- IQVIA. Patient Support Programme (PSP) The art of the possible. IQVIA publication; 2023.

- Presseau J, Byrne-Davis LM, Hotham S, et al. Enhancing the translation of health behavior change research into practice: a selective conceptual review of the synergy between implementation science and health psychology. Health Psychol Rev. 2022;16(1):22-49. doi:10.1080/17437199.2020.1866638