Assessing the Impact of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s Real-World Evidence Framework on Health Technology Assessments

Rebecca Mackley, PhD; Rhiannon Green, MRes; Rhiannon Teague, MRes; Medha Shrivastava, MSc; Steady Chasimpha, PhD, Maverex, Newcastle, England, United Kingdom

Introduction

Real-world evidence (RWE) is generated from healthcare data collected outside the context of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).1 Sources of RWE can include electronic health records, registries, claims/billing data, digital wearables, and even social media.2 RWE can optimize and complement the design of RCTs by extending data collection and reducing financial burden and risk and by providing more generalizable insights into the safety, usage, and effectiveness of medicinal interventions in real-world settings. RWE can be particularly useful in instances where there is insufficient clinical trial data to demonstrate the value of an intervention at the time of reimbursement decision.3,4 However, there are several concerns regarding the use of RWE in Health Technology Assessment (HTA), including potential increased bias and poorer methodological quality.2

To combat this, payers worldwide have implemented frameworks to improve understanding and enhance the quality of RWE, including England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), who introduced their RWE framework on June 23, 2022.1 This framework aimed to improve the quality of RWE used in decision making and help identify where RWE can reduce uncertainties.1

This article reviewed the use of RWE in NICE technology appraisals (TAs) in the 18 months pre- and postimplementation of the NICE RWE framework. TAs published on the NICE website between January 1, 2021 and January 1, 2024 were identified and categorized as being pre- (01.01.2021–23.06.2022) or postframework (24.06.2022–01.01.2024). If the clinical section of the TA included RWE, details of the NICE recommendation, disease area, study type (observational, retrospective, etc), study location, and reasons for inclusion were recorded. TAs were excluded if they had been terminated or if they were treatment guideline updates from TAs originally published more than 5 years ago. The outcomes of TAs include the following possibilities: the drug may be recommended for use, not recommended for use, or, in the case of oncology products, NICE may opt for an additional decision pathway by recommending the drug for use within the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF; a managed access agreement requiring further RWE collection to address clinical uncertainty).5 It was also noted whether the RWE included in the TA was used as the main source of evidence or as supporting evidence. RWE was defined as main evidence if it was mentioned in the final NICE guidance as a key evidence source for decision making and as supporting evidence when it was either mentioned elsewhere in the NICE guidance or only included in the committee paper(s). In cases where multiple sources of RWE were used, these parameters were recorded for each source of RWE within the TA.

There are several concerns regarding the use of RWE in HTA, including potential increased bias and poorer methodological quality.

Use of RWE within NICE TAs pre- and postimplementation of the RWE framework

In the 18 months preimplementation of the RWE framework, 103 TAs were published, and 108 TAs were published postimplementation. RWE was used to inform clinical effectiveness in 27% (28/103) of TAs preframework, and in 31% (33/108) postframework, representing a slight increase in RWE use postframework.

RWE use in TAs by disease category

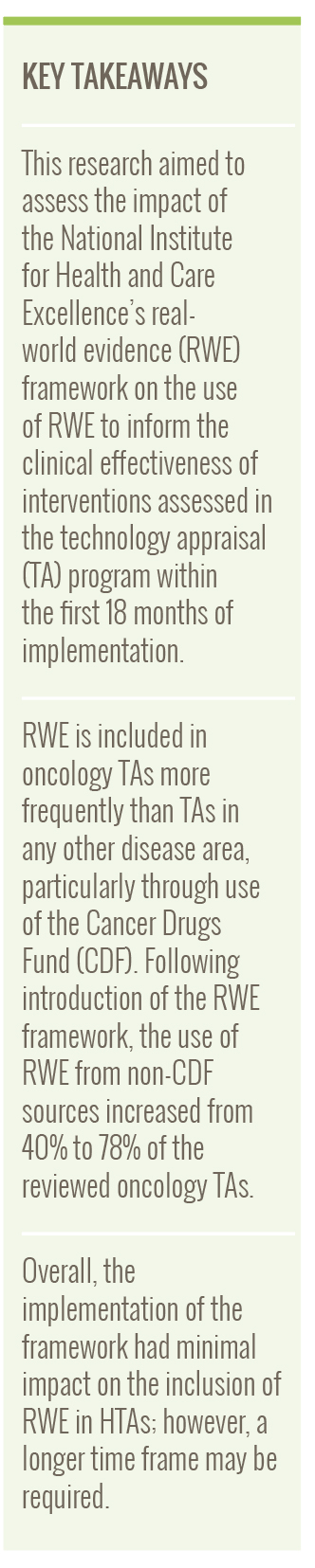

TAs for oncology products utilized RWE more frequently than TAs for nononcology products preframework (oncology versus nononcology; 20 [71%] versus 8 [29%]) and postframework (oncology versus nononcology; 18 [55%] versus 15 [45%]). Oncology TAs were further categorized based on whether they used RWE from the CDF, such as the Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy (SACT; a database of all disease-modifying cancer treatments delivered by National Health Service [NHS] England providers6) dataset (Figure 1). The proportion of oncology TAs using the CDF SACT dataset substantially decreased pre- to post-framework, from 60% (12/20) to 22% (6/18). However, there was also a slight decrease in the number of oncology TAs using RWE overall. Key nononcology disease areas utilizing RWE included cardiovascular, autoimmune, respiratory, and kidney diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. NICE TAs including RWE published pre- and postimplementation of the NICE RWE framework, by TA disease category

RWE study types utilized in TA submissions

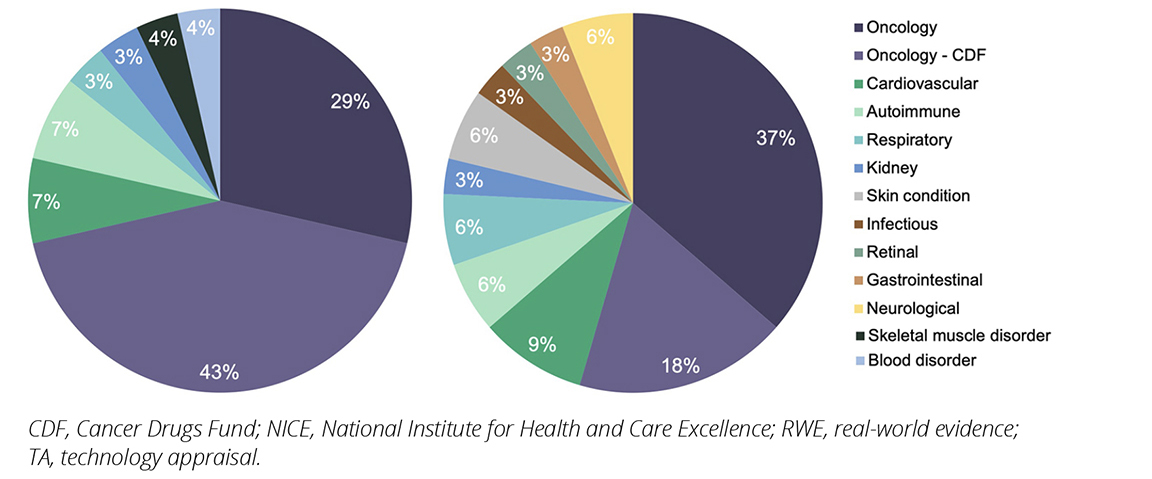

Across all disease categories, the types of RWE used in TA submissions pre- and postintroduction of the framework included the CDF SACT (43% [12/28] versus 18% [6/33]), retrospective studies (14% [4/28] versus 30% [10/33]), other registries (11% [3/28] versus 15% [5/33]) and other observational studies (32% [9/28] versus 36% [12/33]); eg, non-interventional and prospective studies; Figure 2). The use of the CDF dataset decreased postframework, while the use of RWE from other sources all appeared to increase, particularly retrospective studies. This may indicate a shift in the types of real-world studies used following publication of the NICE RWE framework.

Figure 2. Proportion of NICE TAs including RWE published pre- and post-implementation of the NICE RWE framework, by study type

How prominently is RWE used to support TA evidence submission

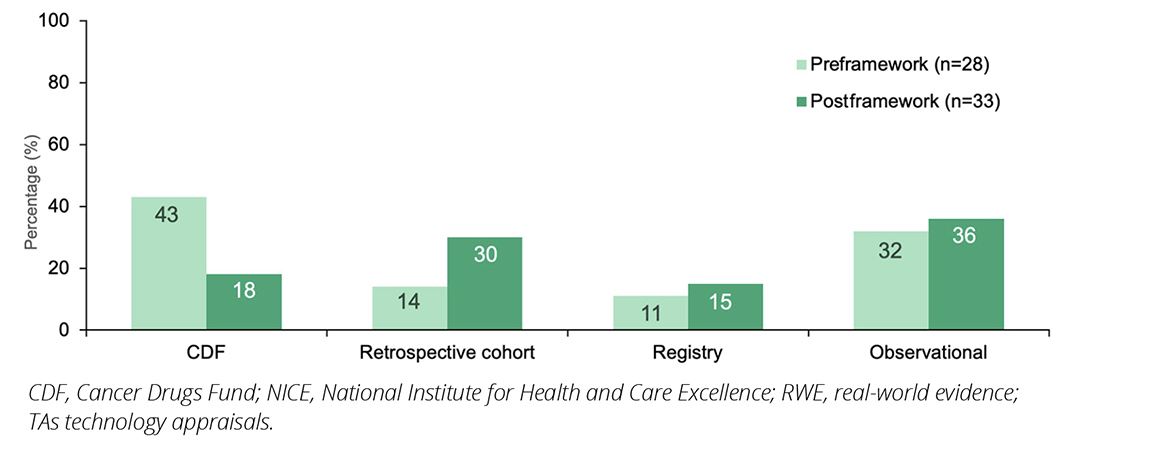

Of the 61 TAs that included RWE, approximately two-thirds (64% [39/61]) used RWE as a main source of evidence. While RWE was utilized as a main source of evidence both pre- and post-framework, the proportion decreased postframework (pre-framework 71% [20/28] versus postframework 58% [19/33]; Figure 3).

Figure 3. NICE TAs including RWE published pre- and postimplementation of the NICE RWE framework, by whether the RWE comprised the main or supporting evidence

Reasons for inclusion of RWE in TAs

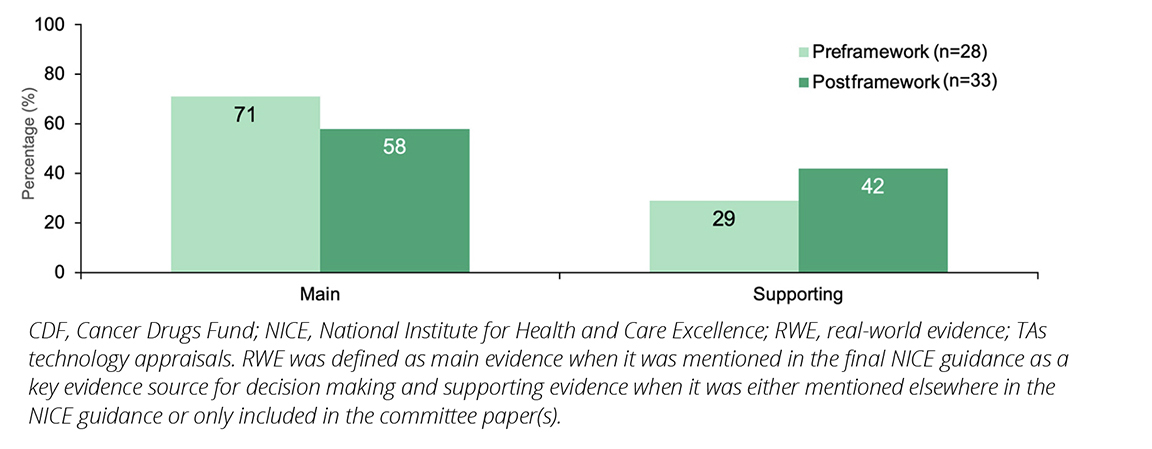

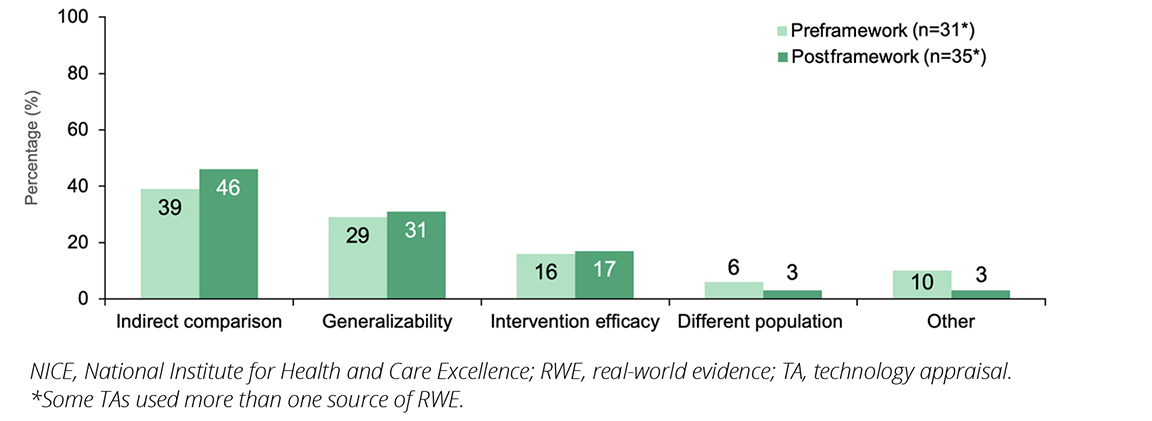

In this analysis, the most common reasons for RWE inclusion both pre- and postframework were to inform indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs; 39% versus 46%) and to demonstrate generalizability of the evidence to NHS clinical practice (29% versus 31%; Figure 4). Often the SACT database was used to demonstrate generalizability to clinical practice in oncology drugs. Lack of generalizability on the use of a health technology in the NHS is often a key limitation in TAs.

Other reasons for the inclusion of RWE were to provide further evidence for intervention efficacy (16% versus 17%) and to address differences in populations (6% versus 3%; ie, where there are differences in characteristics between the main trial population and the target population of the TA submission). Examples include the use of phenylketonuria registries to provide evidence for the sustained and durable efficacy of a drug to treat hyperphenylalaninemia beyond the length of the RCTs (TA729),7 and the use of RWE studies to demonstrate the efficacy of an asthma intervention in a subpopulation for which the RCTs did not provide sufficient evidence (TA751).8

Figure 4. NICE TAs including RWE published pre- and post-implementation of the NICE RWE framework, by reason for inclusion

The formation of ITCs remained the most common use of RWE both pre- and post-framework. This likely reflects the use of ITCs to create comparisons where trial comparators did not reflect the current NHS standard of care and in cases of single-arm trials.

Conclusions

Overall, TAs for oncology products included RWE more frequently than any other disease area (62% compared with 8% for cardiovascular, 7% autoimmune, etc). Challenges associated with conducting RCTs in rarer tumor types, regional discrepancies in the standard of care, and the availability of RWE sources, including the CDF SACT dataset, may be drivers for this.9,10 A contractual requirement of CDF funding includes the submission of treatment activity to the SACT dataset, so RWE data is available and included in the resubmission.11

While the NICE framework provides a structured approach to incorporating RWE into technology appraisals, challenges remain surrounding the lack of clear thresholds for evidence acceptability or suitability.

In the future, the proportion of non-oncology TAs using RWE may increase due to the introduction of the Innovative Medicines Fund (IMF), a second NICE-managed access option. Building on the success of the CDF, the IMF aims to support access to nononcology drugs through collecting data needed to address uncertainty in their evidence base.12 One of the key principles of the IMF is to ensure there is equal access to the latest medicines for both patients who have cancer and those who do not have cancer.13

While the NICE RWE framework provides a structured approach to incorporating RWE into TAs, including offering guidance on study design, data quality, and methodological rigor, challenges remain surrounding the lack of clear thresholds for evidence acceptability or suitability. To increase the use of acceptable RWE in future, NICE could develop more robust standards for RWE use; ensure alignment of the framework with regulatory agencies, including the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency; and offer early engagement opportunities with developers. Consequently, developers could proactively integrate RWE studies into their evidence generation plans.

In conclusion, while there were variations in the type of study and the disease areas using RWE for TA submissions, the overall use of RWE has remained consistent since the implementation of the RWE framework. A longer timeframe is likely needed to assess the true impact of the framework on the use of RWE. It is possible that many of the TAs in this review were designed prior to the introduction of the framework and in the future, and we may see more RWE specifically designed to meet framework requirements.

References

- Introduction to real-world evidence in NICE decision making. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd9/chapter/introduction-to-real-world-evidence-in-nice-decision-making. Published June 23, 2022. Accessed October 13, 2023.

- Dang A. Real-world evidence: a primer. Pharm Med. 2023;37(1):25-36. doi:10.1007/s40290-022-00456-6

- Naidoo P, Bouharati C, Rambiritch V, et al. Real-world evidence and product development: Opportunities, challenges and risk mitigation. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(15-16):840-846. doi:10.1007/s00508-021-01851-w

- Impact of RWE on HTA Decision-Making. IQVIA. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/impact-of-rwe-on-hta-decision-making. Published December 6, 2022. Accessed April 16, 2024.

- Cancer Drugs Fund. National Health Service (NHS) England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/cdf/. Accessed April 16, 2024.

- Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy (SACT) data set. National Disease Registration Service. https://digital.nhs.uk/ndrs/data/data-sets/sact. Accessed April 16, 2024.

- Sapropterin for treating hyperphenylalaninaemia in phenylketonuria. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta729. Published September 22, 2021. Accessed August 30, 2024.

- Dupilumab for treating severe asthma with type 2 inflammation. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta751. Publshed December 8, 2021. Accessed May 30, 2024.

- Kumar P. PRO91 Utility of real-world evidence data to support market access of rare oncology indications in eu5. Value Health. 2019;22:S857. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2019.09.2421

- Di Maio M, Perrone F, Conte P. Real-world evidence in oncology: opportunities and limitations. The Oncologist. 2020;25(5):e746-e752. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0647

- Systemic anti-cancer therapy dataset : Escalation process for non-compliance. NDRS. https://digital.nhs.uk/ndrs/data/data-sets/sact/sact-escalation-process. Accessed August 29, 2024.

- Briefing on the Innovative Medicines Fund. Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI). https://www.abpi.org.uk/publications/briefing-on-the-innovative-medicines-fund/. Published January 31, 2022. Accessed April 24, 2024.

- The Innovative Medicines Fund Principles. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/B1686-the-innovate-medicines-fund-principles-june-2022.pdf. Published June 6, 2022. Accessed April 30, 2024.