This Technology Should Be Compared With?... And for Whom? The Digital Health Population Conundrum

Robert Malcolm, MSc, Maisie Green, MRes, Rebecca Naylor, MSc; Hayden Holmes, York Health Economics Consortium, York, England

Background

Health interventions delivered through digital technologies, such as smartphones, web-based resources, and text messaging, have become increasingly common over the past decade. Such digital health technologies (DHTs) can be used for treatment, diagnosis, data analysis (scanners and monitors), and for improving system efficiencies.1 As DHTs become more popular and their efficiency improves, they will begin to augment or replace traditional healthcare interventions. Therefore, economic evaluation studies are of central importance for making informed decisions about DHTs. However, DHTs present methodological challenges for economic evaluation, which have been observed with other healthcare interventions, but are more common for DHTs.

DHTs can often be used across a wide range of pathways, rather than in the treatment of specific health conditions. Consequently, a DHT may change the existing processes or pathways of care, which can create difficulties in finding the relevant comparator in economic evaluation.2 The comparators may also differ at local, regional, and national levels, particularly where a DHT is replacing part or all of a face-to-face care pathway. Thus, it is important to consider the comparator used in economic evaluation of a DHT and to build in flexibility for this to be easily adapted to more local settings.

A second challenge for economic evaluation is the difference in population indication for interventions. DHTs may be used on a wide-ranging population, rather than being defined by the therapeutic indication, as is usually the case with pharmaceuticals. Although DHTs share similar features to medical devices on the indicated population, they are still even more likely to be used across a wider range of indications than medical devices. For example, a DHT may be used across all people suffering with chronic pain, whereas a medical device may only be used for specific types of pain. Hence, understanding how the population may vary needs to be taken into consideration when evaluating a DHT.

Health economic evaluation can be used to highlight the impact of investment in DHTs while facilitating efficient use of limited resources. However, economic evaluation applied inconsistently or illogically—such as not using the most appropriate comparator or population—can hinder the decision-making process.

This article aims to describe how these issues can be approached when evaluating the health economic impact of DHTs. Along with this, the paper will discuss other potential challenges, including the implementation of DHTs into the National Health Service.

Our Approach

A pragmatic literature review was undertaken to find research that had sought to provide clarity or had outlined a framework for the evaluation of DHTs. This was conducted using unstructured searches on PubMed and Google Scholar. Extraction focused on frameworks that identified issues and/or solutions associated with either appropriate populations or comparators for DHTs.

Following this, a series of expert panel discussions and interviews were undertaken whereby the approaches to evaluating DHTs, including the approach to capturing the population and selecting the relevant comparators, were discussed. The interviews were informed by the pragmatic literature review so that we could determine if the experts agreed or disagreed with the published literature. The discussions and interviews captured people with a range of experience, including health economic consulting as well as academic and public sector perspectives.

"Digital health technologies may be used on a wide-ranging population, rather than being defined by the therapeutic indication as is usually the case with pharmaceuticals."

Lessons Learned

Regardless of the purpose of the DHT, the choice of comparator will be a function of how the intervention interacts with nondigital healthcare.3 For example, the DHT may complement or substitute other types of healthcare delivery or administration systems. In settings where the intervention is implemented in an area where a DHT is already used, the relevant comparator may be simpler to identify, unless the new DHT has a wider aspect that the current DHT does not cover.2

Discussions with the experts highlighted a key issue linking the population and comparator: whether the DHT distorts the population in the care pathway. For example, if a DHT increases access to a care pathway, then it may result in more people using the pathway, which could change the underlying population (such as by disease severity or age). In some cases, changing the population may also change what is considered “standard care,” especially if the severity of the population changes. In some cases, the DHT may only be adjunct to standard care, meaning that the care pathway has not changed. Hence, it is important that any economic evaluation can incorporate and reflect differences in characteristics.4 Clinical advice should be sought when designing any evaluation plan to understand the possible “spillovers” that may happen with the DHT.

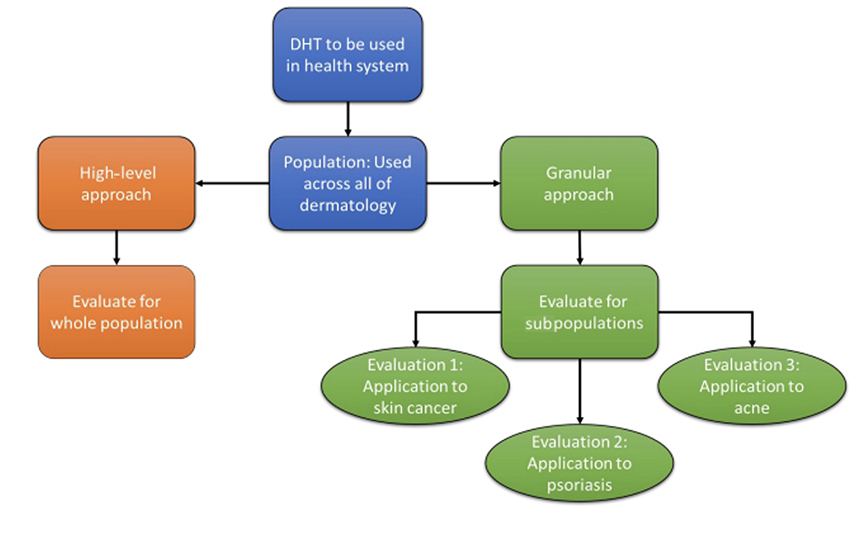

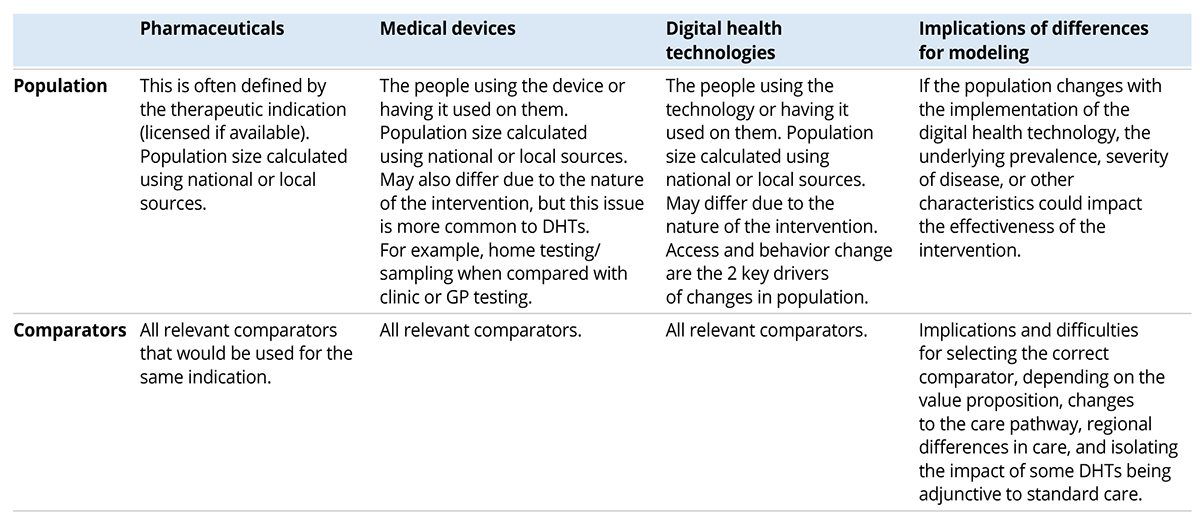

The discussions also identified 2 approaches to conceptualizing economic evaluations of DHTs where the scoped population was less specific. An example of these 2 approaches that looks at a DHT for use in dermatology is visually displayed in Figure 1. The first approach is to narrow the population in the evaluation to a specific indication, omitting some of the DHT’s potential benefit (a granular approach). The second is to keep the population as broadly defined as possible, but to simplify the health economic evaluation to key costs, resource use, and health outcomes that are generalizable across a range of conditions and pathways (pragmatic approach). This approach may lead to omitting potential benefits through simplifying the decision problem. The appropriate choice is likely to be decided on a case-by-case basis for each specific DHT, depending on the variation and generalizability of the care pathway. Table 1 provides a summary of the different populations and comparators used in different interventions. This table shows how broad the comparator can be for DHTs compared with other interventions, as well as how varied the population can be that the DHT is used on.

Figure 1. Evaluation of DHTs with wide populations.

Table 1. Comparison across interventions.

Key Evaluation Considerations for Now and the Future

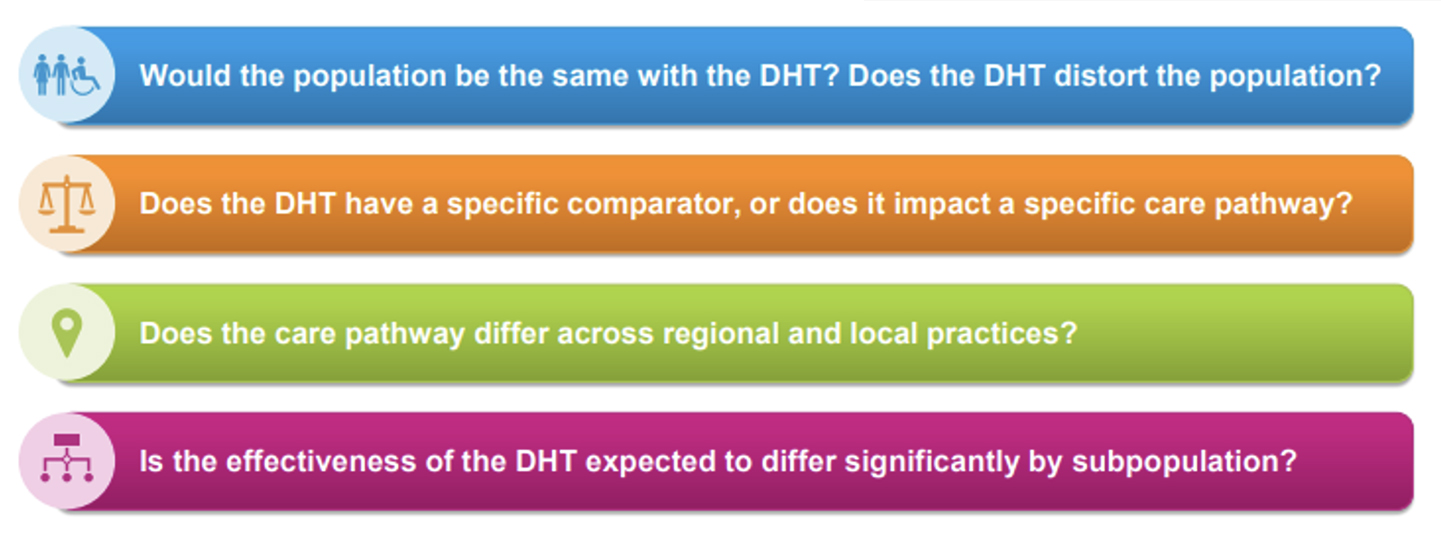

Important considerations for DHT evaluation are listed in Figure 2. DHTs may be used on a wide-ranging population, rather than being defined by the therapeutic indication as is usually the case with pharmaceuticals. Population subgroups, where the effectiveness of the DHT may be expected to differ, must also be taken into consideration. Furthermore, DHTs may also subvert care pathways, meaning that the population and underlying prevalence may be different for DHTs with respect to the comparator, particularly where the DHT changes the patient access within a care pathway. Understanding how the population may vary needs to be taken into consideration when evaluating a DHT.

Figure 2. Key considerations for DHT evaluation.

Identifying the relevant comparator can be a difficulty in evaluating DHTs. Comparators may differ at local, regional, and national levels, particularly where a DHT is replacing part or all of a face-to-face care pathway.

Future considerations could include the development of a centralized body for DHT evaluation. In England, this could be divided between NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). Other countries may also wish to appoint a centralized body and team dedicated to these evaluations. Each DHT should have a measured scoping approach to determine the appropriate balance between granularity and pragmatism to inform decision makers.

Summary

DHTs may need much more localized, flexible models and a detailed scoping of the population and comparators than other healthcare interventions. To identify the full benefit of a DHT, evidence generation should look to capture broader populations where possible. Decision makers should be supported to develop a framework to identify and discuss the risk, generalizability, and unquantifiable benefit of adopting DHTs with wider populations. Future research should consider how distorting populations within care pathways from implementing DHTs could impact study design and data collection in order to determine the true effectiveness of DHTs.

References

- Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/corporate/ecd7/chapter/section-a-technologies-suitable-for-evaluation-using-the-evidence-standards-framework. Published December 10, 2018. Updated August 9, 2022. Accessed May 14, 2024.

- Wilkinson T, Wang M, Friedman J, Gorgons M. A framework for the economic evaluation of digital health interventions. World Bank Group. Published April 2023. Accessed May 16, 2024.

- Gomes M, Murray E, Raftery J. Economic evaluation of digital health interventions: methodological issues and recommendations for practice. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(4):367-378.

- Guo C, Ashrafian H, Ghafur S, Fontana G, Gardner C, Prime M. Challenges for the evaluation of digital health solutions—a call for innovative evidence generation approaches. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:110.