Discrete Choice Experiments

Section Editor: Koen Degeling, PhD

In

this edition of Methods Explained, we are covering discrete choice experiments

based on a conversation with Janine van Til and Verity Watson. Janine van Til,

PhD is an Associate Professor in health preference research at the department

of Health Technology and Services Research of the University of Twente in The

Netherlands, and active member of the ISPOR Special Interest Group on health

preferences research and the Internation Academy of Health Preference Research.

Verity Watson, PhD is a Senior Economist at RTI Health Solutions and Honorary

Professor at the Health Economics Research Unit of the University of Aberdeen

in the United Kingdom.

In

this edition of Methods Explained, we are covering discrete choice experiments

based on a conversation with Janine van Til and Verity Watson. Janine van Til,

PhD is an Associate Professor in health preference research at the department

of Health Technology and Services Research of the University of Twente in The

Netherlands, and active member of the ISPOR Special Interest Group on health

preferences research and the Internation Academy of Health Preference Research.

Verity Watson, PhD is a Senior Economist at RTI Health Solutions and Honorary

Professor at the Health Economics Research Unit of the University of Aberdeen

in the United Kingdom.

We welcome your feedback on this article and any suggestions for methods to be covered in future editions. Send your comments and suggestions to the Value & Outcomes Spotlight Editorial Office.

What are discrete choice experiments and what can they be used for?

Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are

part of the group of stated preference methods. They are based on several ideas

about how people make decisions between competing options. The first principle

is that people always choose the option with the highest perceived value in

choosing between products or services. Second, people value the attributes of

the options rather than the options themselves, and their preferences are based

on the desirability of those attributes. Third, people are willing to trade (ie,

accept) negative outcomes on certain attributes to obtain positive outcomes on

others.

Within the field of health economics

and outcomes research, DCEs are primarily used to understand the relative

importance of attributes of alternative health or healthcare options (eg,

health states, treatments, healthcare services), and the trade-offs people are

willing to make between them. This has several use cases, including the

assessment of benefit-risk trade-offs, for example in regulatory decision

making, the assessment of the willingness to pay for different benefits, and

health state evaluation. They can also be used in implementation science to

understand what is important when introducing a healthcare service, or during

development to understand the potential benefit of a new intervention.

Although DCEs have been typically used to understand preferences on a group level, they can be used to understand variation in preferences within a certain patient population (ie, preference heterogeneity). For instance, this can help to identify subgroups of patients who are willing to accept a higher risk to achieve higher benefit from treatment. Finally, DCEs have been applied on an individual level to support patients in deciding between treatment options by helping them to understand what is important to them.

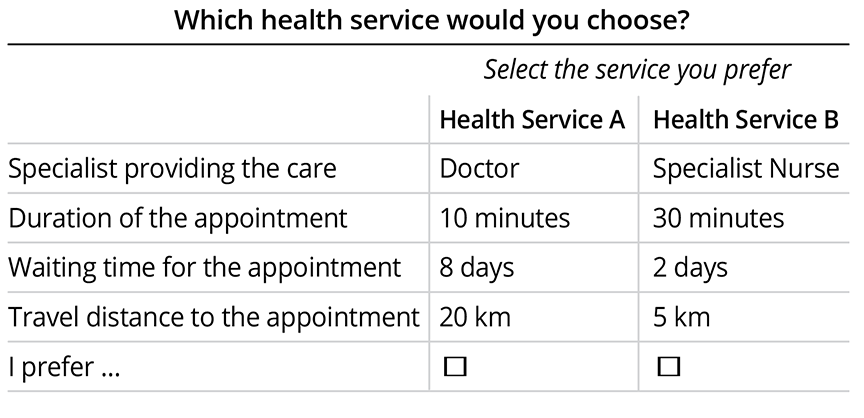

On a practical level, how do DCEs work?

As a prerequisite, it should be

possible to describe the (range of) healthcare products or services of interest

using attributes, with each attribute having different levels that describe the

possible outcomes. For example, when considering a medicinal product,

attributes can be the effectiveness (eg, probability of 5-year survival), risk

of a severe adverse event (eg, the proportion of patients experiencing the

event), and mode of administration (eg, oral or intravenous). When evaluating a

healthcare service, attributes can be the time spent with a healthcare provider

(eg, in minutes), type of healthcare provider (eg, doctor or specialist nurse),

and the travel distance to see the provider (eg, in kilometers or miles).

Extensive qualitative research is needed to appropriately describe the options,

their attributes, and the levels of these attributes.

Different combinations of attribute levels are generated using experimental design methods, aiming to cover the entire spectrum of options within a manageable number of questions. In each question, study participants are presented with 2 or more hypothetical options described by the attribute levels and asked which option they would choose, typically through a survey. In a typical study, participants answer between 8 and 16 questions. An example of what such a question may look like is presented in the Figure.

Figure. Illustration of a hypothetical discrete choice experiment.

Several outputs are obtained from analyzing the responses to a DCE survey. First of all, the relative importance of the attributes is obtained. This is a measure of the influence of each attribute on the preference for the options. Second, one can obtain the marginal rate of substitution that gives information on the extent to which people are willing to trade outcomes between 2 attributes. This can be used to determine the willingness to wait for an appointment to talk to a doctor (see example above), but likewise, it can be used to estimate the willingness to pay, the maximum acceptable risk for a certain benefit, or the minimum required benefit that is needed to offset a certain risk. Finally, the preference share can be obtained. This can be used to assess the uptake of a certain health intervention or service given the alternatives in the market and give insight in how changing certain attributes of an intervention is expected to impact uptake.

What makes DCEs different from other preference research methods?

There is a fundamental difference between stated preference research, for which DCEs are used, and revealed preference research. The latter is based on choices that have been observed in practice. These are a more reliable estimate of actual choices but come with 2 important limitations: (1) no understanding is obtained of why people made a certain choice, and (2) the findings are limited to the options available in practice at the time of the decision, which may be different from those of interest. DCEs address these limitations.

Another method that comes to mind to address these limitations may be interviews. However, the value of interviews to understand preferences that are representative for a patient population is often limited by the sample size and the inherent selection of the participants. Rating scales and similar survey questions are often used to understand the importance of attributes or to elicit direct preferences for healthcare products or services. However, these types of questions do not incorporate trade-offs, making their findings less valid for understanding what drives the preferences and the value of health and healthcare from a methodological perspective.

One may also compare DCEs to multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA). While DCEs are used to understand why people have certain preferences, MCDA aims to assist people in making more (rational) decisions. Eliciting the relative importance that people attach to certain attributes that drive these decisions is an important step in an MCDA, and the relative importance of attributes, as derived from a DCE, could be used for this.

What are the steps in developing a DCE?

After defining the research question and doing formative research to identify what drives people’s choices, the most important step in designing a DCE is describing the options using attributes and levels. One needs to balance the number of attributes that is feasible in terms of participant burden, while ensuring that all attributes that are relevant to the decision are included. Like any survey, a DCE should be designed with care and extensively pilot tested to ensure that participants’ understanding of the attributes and instructions is correct. In the end, the relevance of findings is determined by the representativeness of the participant sample to the research question and, hence, careful consideration should be given to the dissemination of the survey.

"In the end, the relevance of findings is determined by the representativeness of the participant sample to the research question and, hence, careful consideration should be given to the dissemination of the survey."

To what extent are DCEs being used and what challenges remain?

DCEs are used in regulatory decision making to inform benefit-risk trade-offs. The US Food and Drug Administration has guidelines on how to perform stated preference research, including DCEs, which includes recommendations on how to incorporate the findings in the regulatory process. The European Medicines Agency does not have specific guidelines for the latter but has endorsed multiple project groups in performing methodological work.

In terms of health technology assessments, the number of applications with clear impact on reimbursement decisions remains low. However, there are some examples where a DCE provided information that was considered in the decision making of agencies. For example, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia has considered results from a DCE in their decision making, albeit with several caveats.1

One of the important limitations of DCEs as a stated preference methodology is that it remains unknown whether the respondent would actually make the decision that is predicted by their stated preferences. However, there is an increasing body of literature that provides insights into the consistency of stated and revealed preferences. Another challenging aspect of DCEs is balancing the scope of the experiments in terms of the number of attributes and levels, the efficiency of the survey, and the cognitive burden to the participants. Experience of the researchers is instrumental in striking the right balance.

This edition of Value & Outcomes Spotlight focuses on Alzheimer’s disease. Are there specific considerations regarding DCEs in this disease area?

As current treatment options for Alzheimer’s disease offer relatively modest incremental benefits, DCEs can be very helpful in assessing the benefit-risk trade-off for these treatments. Quality of life is very important to patients with Alzheimer’s disease, so it is important to know what trade-offs they are willing to make to give them the best possible life they have in front of them. DCEs may also provide insights that can be used to inform the design of healthcare services for patients, as well as supporting services for caregivers.

Carefully considering the design of DCEs becomes even more important in the context of Alzheimer’s disease, because keeping the survey as simple as possible is critical to enable patients to participate as their disease progresses. This is a delicate balancing act, as one wants to give a voice to patients with decreased cognitive function, but at the same time wants to avoid asking them to carry out tasks that are too complex. If patients themselves are not able to complete the DCEs, their caregivers can complete them on their behalf as proxies.

What are some key references for further reading?

For those wanting to read one or more case studies, Morrish et al recently identified 9 studies of DCEs in Alzheimer’s disease.2 For those interested to learn more about how to perform DCEs, ISPOR Task Force groups have published several guidance papers on DCEs,3,4 as well as a more recent perspective on increasing the usefulness and impact of patient-preference studies.5

References

- Exenatide Public Summary Document (PSD) July 2015 Meeting. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. 2015. https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2015-07/exenatide-psd-july-2015. Accessed April 19, 2025.

- Morrish N, Fox C, Reeve J, et al. Exploring health and social care preferences for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Aging Ment Health. 2025;17:1-12.

- Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3-13.

- Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300-15.

- Bridges JFP, de Bekker-Grob EW, Hauber B, et al. A roadmap for increasing the usefulness and impact of patient-preference studies in decision making in health: a Good Practices Report of an ISPOR Task Force. Value Health. 2023;26(2):153-162.