Value Assessment in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Equity

Anirban Basu, PhD, MS, Department of Health Economics, University of Washington School of Pharmacy, Seattle, WA, USA; Nancy Lynn, MA, Senior Vice President, Strategic Partnerships, BrightFocus Foundation, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Susan Peschin, MHS, President and CEO, Alliance for Aging Research, Washington, DC, USA; Jason Resendez, Executive Director, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s Center for Brain Health Equity, Washington, DC, USA

Equity as an Essential Value Consideration

The hardship of Alzheimer’s disease is not only immense—but highly unequal. The disease’s health and economic consequences fall disproportionately on certain demographics, including older adults, women, people of color, and those with lower levels of education and wealth.

Given these disparities, one of the main benefits of a novel disease-modifying Alzheimer’s therapy would be its potential to improve health equity. Yet this potential is not considered in traditional value assessment frameworks. With several Alzheimer’s therapies in phase III clinical trials, now is the time to consider how value assessments can incorporate elements to reflect the value of making society more equitable, ethical, and inclusive. These elements could be included alongside traditional cost-effectiveness metrics to inform deliberative processes on value decisions, leading to more robust deliberation that fully captures key considerations like equity.

The inequities of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias can be traced across demographic lines. Most evidently, Alzheimer’s disease disproportionately affects older adults. In the United States, 10% of Americans 65 years or older—or 5.8 million people—live with Alzheimer’s disease, and, within that group, prevalence rates increase with age.1 Overall, 80% of Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease are 75 years old or more.1

Racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease are also stark. Older Black Americans are approximately twice as likely to have Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia as older White Americans, while older Latinos are about 1.5 times more likely.1 Many factors contribute to this disproportionate prevalence. Black and Latino populations have higher rates of risk factors like cardiovascular disease and diabetes, as well as socioeconomic risk factors like lower levels of education, higher rates of poverty, and greater exposure to discrimination.1

Alzheimer’s disease also has an outsized impact on women. Two-thirds of Americans with dementia are women, and a woman has about a 20% chance of developing the disease during her lifetime.2 A man, however, only faces about a 10% risk over the course of a lifetime.2 And two-thirds of caregivers (spouses or children) are women, providing the vast majority of the 18.6 billion hours of unpaid dementia care in the United States, valued at almost $244 billion.1 Many of these women must also care for children, as part of the “sandwich generation,” and many reduce their work hours or drop out of the workforce altogether because of these care responsibilities.3

Even with these stark demographic trends, traditional value assessment frameworks do not account for inequities or the potential for new therapies to promote health equity. This is a missed opportunity. Widespread access to an effective disease-modifying therapy has the potential to reduce the disproportionate impact on women of all ages, communities of color, and older adults. The benefits of an innovative treatment to these demographic groups should not be overlooked.

This paper explores how equity considerations could be better integrated into value assessment frameworks by examining several key topics:

• The limitations of traditional value assessment and QALYs, as seen through an equity lens

• The growing and disproportionate impact of Alzheimer’s disease on women and Black and Latino communities, the barriers to “brain health equity,” and the importance of addressing racial inequities

• Different perspectives on what equity means for an eventual disease-modifying Alzheimer’s treatment

• Real-world impacts and potential new models to better incorporate equity into future Alzheimer’s value assessments, deliberations, and decisions

The goal of this article is to spark discussion about health equity in value assessment. Value frameworks must better reflect health equity to not only enhance the benefits of new Alzheimer’s treatments, but also protect the most vulnerable people in our society.

The Challenges of Equity: QALY Controversies, Distributive Justice, and Incomplete Valuation

As discussed in the first piece of this supplement, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) are the traditional metric for cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) within value assessment.4 Cost-per-QALY analyses are used to compare the value of treatment options among different disease areas and guide decisions about how to allocate resources, when considering a desire for a framework to equate conditions and resources and facilitate “objective” decision making. The best return on investment can be considered as the most favorable cost per QALY. However, when viewed through a lens of equity, QALYs have been criticized because they can be used in a way that effectively discriminates against older, sicker patients in evaluating treatments that extend life expectancies. Additionally, like any other single health outcomes metric, cost per QALY, by itself, cannot and does not advance distributive justice and overlooks the functional benefits of better health.

First, cost-per-QALY evaluations effectively place a lower value on the lives of certain patients, especially those who are older or living with comorbid conditions. A QALY measures both the length and quality of life that a health technology will provide to a patient. Therefore, people living with comorbidities or a disability, as is common in older patients, are assigned a lower initial quality of life in the QALY framework, which effectively places a lower value on extending their lives compared to a younger, healthier patient who experiences the same gains in life expectancy.

Second, cost-per-QALY evaluations only consider the utilitarian principle of maximizing total benefit. It leaves out many other questions of distributive justice, which concerns the equitable allocation of resources. For example, cost per QALY does not consider the size of the population represented by the condition or intervention and is unfit to address questions of whether it is better to provide large benefits to a small number of people, or small benefits to a large number of people. Further, it does not support examinations of the value that should be placed on benefiting groups that have been historically marginalized and under-served. These are the difficult questions of distributive justice. Answering them requires carefully weighing societal values, priorities, and needs. But traditional value assessments do not have a clear mechanism to answer these difficult questions.

Third, cost-per-QALY evaluations do not capture a treatment’s functional benefits beyond lifespan and quality of life, raising concerns about incomplete valuations. For example, a treatment can have productivity benefits by enabling patients and caregivers to stay in the formal workforce, do productive work in their household, volunteer in their community, or provide other forms of value to society. In the case of cognitive decline, an effective treatment could provide broader benefits for a patient’s quality of life that are not captured in standard health-related quality of life instruments. However, these functional benefits are not measured by typical cost-per-QALY evaluations. Moreover, a treatment that slows the progression of Alzheimer’s disease can have important quality of life benefits for caregivers, reducing physical, emotional, and financial strains.

To address these concerns, supplements and alternatives to QALYs have been developed. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) has proposed a secondary measure, the Equal Value of Life Years Gained (evLYG) metric.5 The evLYG values all life years gained equally, regardless of the patient’s starting quality of life. However, this also means that the evLYG metric can undervalue treatments that improve quality of life.

Another alternative is health years in total (HYT), developed by researchers at the University of Washington. Under this metric, a treatment’s life expectancy effects are added to its quality-of-life effects.6 By taking this additive approach, rather than the multiplicative approach that characterizes QALY analysis, HYT analysis avoids the devaluation of patient life years that occurs when utility weight is multiplied by life years. In doing so, the HYT framework leads towards more equitable outcomes for patients with lower quality of life, enabling them to fully benefit from therapies that increase life expectancy.

Finally, despite the criticisms of CEA and QALYs, it should be noted that such analyses can be effective if employed as one consideration among many. Indeed, no guideline or recommendation that calls for the use of CEA states that CEA should be the sole factor on which such resource allocation decisions are made. CEA results can be included in a broader set of metrics and perspectives that inform a deliberative process’s ultimate decisions. Many of the criticisms of CEA can be addressed through such deliberative processes, which could include metrics on health equity and other key elements of value, as well as perspectives shared by those who are most directly and disproportionately affected by Alzheimer’s disease.

Barriers to Brain Health Equity: The Unequal Impacts of Alzheimer’s Disease on Women and Communities of Color

Since value assessment frameworks are a tool developed to help payers allocate resources to achieve socially desirable goals, value assessors must clearly define their goals and values. One of these goals should be “brain health equity” (ie, the same opportunity for brain health, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or other demographic factors).

Our society is far from achieving this goal, particularly given the disproportionate impacts of Alzheimer’s disease on women and racial and ethnic minorities. As stated previously, women account for a majority of the people with Alzheimer’s disease, provide a disproportionate share of Alzheimer’s care, and bear a severely unequal financial cost, as both patients and caregivers. Of the 5.8 million Americans 65 years and older who live with Alzheimer’s disease, 3.6 million—almost two-thirds—are women.1 Several factors may contribute to this greater prevalence, including longer lifespans, genetic differences, and levels of educational attainment.1

In the United States, approximately two-thirds of Alzheimer’s caregivers are also women, with daughters comprising approximately one-third of caregivers.1 Women who are caregivers also spend more time on care, as 73% of dementia caregivers who provide more than 40 hours of care per week are women, and 2.5 more women than men live full-time with a person with dementia.1 Even more troubling, approximately one-quarter of dementia caregivers belong to the “sandwich generation,” caring for one or more aging parents while taking care of children under 18 years old.1 These heavy caregiving responsibilities often have a significant, complex impact on women. Approximately 19% of women who care for loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease had to quit work to manage their caregiving responsibilities.7 Women caregivers have been found to experience higher levels of depression, impaired mood, and negative health outcomes than male caregivers.1

Women also bear a disproportionate share of the direct and indirect costs of Alzheimer’s disease. The cumulative direct cost of treating women with dementia in the United States from 2012 to 2040 is estimated at around $370 billion, or approximately 70% of cumulative direct costs.7 Indirect costs, such as reduced productivity and workforce participation, associated with women are projected to reach approximately $2.1 trillion between 2012 and 2040, making up approximately 80% of cumulative indirect costs.8

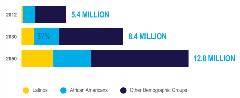

Figure 1. By 2030, nearly 40% of Americans living with Alzheimer's disease will be Latino or African American.

Racial and ethnic disparities are also stark. In the United States, Black and Latino communities account for a growing share of the Alzheimer’s patient population. According to Florida International University and UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, by 2030, nearly 40% of people living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias will be Latino or African American (Figure 1).9

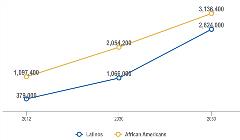

The number of Black Americans living with Alzheimer’s disease is expected to almost double from nearly 1.1 million in 2012 to over 2 million in 2030, and the number of Latinos with the disease is expected to nearly triple from 379,000 to around 1.1 million in the same period.9-11 By 2050, these totals will continue to rise to over 3.1 million African Americans and 2.6 million Latinos (Figure 2).1,10

Figure 2. Alzheimer's disease prevalence among Latinos and African Americans.

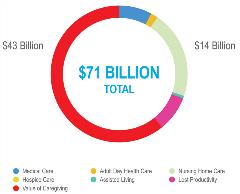

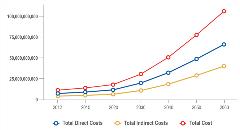

This growing prevalence translates into potentially debilitating costs for these communities, which already face severe socioeconomic disparities. Significantly, much of this cost is indirect, such as caregiving and lost productivity or lost wages, which is not captured by traditional value assessment (Figure 3). For example, in 2012, direct and indirect costs of Alzheimer’s disease for African Americans totaled over $71 billion. In particular, the cost of unpaid caregiving provided by African Americans accounted for more than $43 billion—or approximately 60% of the total cost.10 This economic burden is also geographically concentrated, with 49% of costs accruing in the American South.10

Figure 3: Total direct and indirect costs of Alzheimer’s disease on

African Americans.

If prevalence continues to grow on its current course, so will the economic burden. For Latinos, total direct and indirect costs are projected to steadily rise from approximately $11 billion in 2012 to approximately $30 billion in 2030 and $105 billion in 2060 (Figure 4).11 Again, indirect costs account for a significant share of the total economic burden.

Figure 4: Total direct and indirect costs of Alzheimer’s disease on US Latinos nationally.

Furthermore, these estimates may understate the trends for Black and Latino populations, as they are less likely to have easy access to health systems and may therefore go undiagnosed and remain excluded from data collection. A lack of healthcare access also means that marginalized groups are under-represented in clinical trials. To measure the full promise of new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease—and ensure they benefit diverse communities—clinical trials must better represent racial and ethnic minorities. These data gaps, together with the inequities identified in existing research, clearly show that significant efforts are needed to improve health equity related to Alzheimer’s disease. While value assessment alone is insufficient to drive the necessary progress, incorporating equity considerations into these discussions and decisions can help our society to recognize and work towards the promise of brain health equity.

Measuring Equity: Considerations for a Future Alzheimer’s Therapy

Given the criticisms of the limited cost-per-QALY evaluations and the urgent need for greater brain health equity, what might a more equity-informed approach to a potential new Alzheimer’s therapy look like?

In this case, value assessors would aim to maximize the total societal benefit of a treatment given its cost, or its “efficiency,” while also considering the treatment’s ability to reduce unfair inequality or its “equity.” Taking this approach, a new treatment’s benefits and drawbacks can be charted on an equity-efficiency impact plane. Such a plane can be divided into 4 quadrants, with efficiency impacts on the y-axis and equity impact on the x-axis.12

A new treatment’s potential value can then be divided into 4 categories—win-win, win-lose, lose-win, and lose-lose. In other words, the treatment could: provide cost-effective benefits and improve equity (win-win); fail to provide cost-effective benefits but improve equity (lose-win); provide cost-effective benefits but reduce equity (win-lose); or fail to both provide cost-effective benefits and reduce equity (lose-lose) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The efficiency-equity impact plane.

According to a recent analysis by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of diverse therapies (not specific to Alzheimer’s disease), most new therapies fell into the win-win quadrant, with another large portion falling into the win-lose category.12 Lose-lose and lose-win therapies were both uncommon.13

This framework provides several practical lessons for a potential Alzheimer’s therapy. First, a therapy should be considered most valuable if it both provides broad, cost-effective societal benefits and reduces inequity by addressing the disproportionate impact on women, racial and ethnic minorities, underserved communities, the elderly, and other groups. Second, through an equity lens, there is still value in a treatment that is relatively less cost-effective but reduces health inequity. Third, it is critical to develop strategies to ensure that a new treatment will reach those communities that need it most, in order to reduce inequity.

Finally, it should be noted that this “value-maximizing” approach is just one way of defining equity. Fairness can come in many different forms, and individuals and communities have diverse, varied conceptions of what fairness means. While traditional value assessment focuses on maximizing value, there are 3 other important perspectives on equity: fair shares, moral rights, and fair processes.

Under a fair shares approach, resources are distributed in proportion to patients’ needs, offering each individual a fair chance at receiving needed resources. A rights-based approach assumes that patients have a fundamental right to benefits and care, no matter the cost. This involves concepts like the right to autonomy, the right to be treated with dignity, and the right to nondiscrimination. Fair processes of decision making focus on ensuring that decisions are made in a way that is impartial, accountable, inclusive, and transparent. These perspectives can broaden the discussion of value to include important, but hard-to-quantify concepts and priorities.

Looking Ahead: New Tools to Advance Equity in Alzheimer’s Disease

The equity concepts described above have growing real-world relevance in the Alzheimer’s field, given the increasing likelihood of a new disease-modifying treatment. In fact, there already has been significant discussion and debate on this topic, and there is an ongoing discussion about how best to address the difficult moral questions of equity in future value decisions. New tools and models, including multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) and value-based contracts, offer opportunities to incorporate equity considerations and better reflect the needs and priorities of those with lived experience of Alzheimer’s disease.

As discussed above, QALY-based assessment, when leveraging QALYs alone, can have negative consequences for older, sicker members of society. These concerns were demonstrated in a 2005 decision from NICE that determined cholinesterase inhibitor drugs for the treatment of dementia were not cost-effective and should not be covered for UK’s National Health Service patients.14 NICE acknowledged the effectiveness of these drugs in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, but it ruled that these benefits were not large enough to justify coverage. This decision led to significant controversy, as patient advocates argued that NICE was effectively discriminating against older, sicker people and ignoring the lived experience of those with the disease and their caregivers.

In the years since, there has been growing momentum for alternative tools that aim to address such challenges. One approach is MCDA, a comprehensive and holistic tool that can better incorporate aspects of equity and societal values.15 MCDA is tailored to the decision-making process’s particular objectives and conducted with the input of a range of stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, and ethics committees.16 These stakeholders select the criteria that a given decision aims to achieve—giving a broader set of voices input into value decisions.16

Value-based contracts that consider patient preferences offer another way to address the challenges of traditional CEA.15 Under these contracts, drug manufacturers and payers link coverage and reimbursement to effectiveness and utilization frequency; if a medication works and patients want to use it, utilization frequency will rise. Value-based contracts can also include reauthorization criteria that rely on a clinician’s assessment of whether a patient is still receiving benefit.15 These contracts reduce payer risk of suboptimal purchases, facilitate earlier access to therapies, and offer a more efficient pricing mechanism.15 And, since utilization frequency is measured, value-based contracts can be a catalyst for enhanced real-world medical evidence.15 These alternatives provide potential new directions to better integrate equity considerations and lived experience into future value decisions.

Envisioning a Healthier, More Equal Society

New Alzheimer’s disease therapies can move societies closer to brain health equity. This article offers 4 overarching conclusions:

• Alzheimer’s disease generates disproportionate health and economic impacts on older adults, racial and ethnic minorities, and women, causing societies to fall short of brain health equity.

• QALYs alone do not account for these inequities or the value of treatments that could help to address them.

• Equity is an essential consideration for overall societal welfare, and it must be considered through multiple perspectives.

• Incorporating equity considerations into Alzheimer’s value assessment and related deliberative processes requires evolving current processes and frameworks, potentially with MCDA and value-based contracts.

The next piece in this supplement will complement this article by examining evidence needs in long-term value demonstration.17 We hope that these 3 pieces, taken together, will help evolve frameworks for value assessment in Alzheimer’s disease, including recognizing equity as an essential consideration. •

Richard Cookson, DPhil, MPhil, professor at the Centre for Health Economics and co-director of the Equity in Health Policy Research Group, University of York, contributed to this manuscript.

References

1. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(31):391-460. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12068

2. Colino S. The Challenges of Alzheimer’s and Dementia for Women. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/health/brain-health/info-2020/dementia-women-risk-caregiving.html. Published May 20, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

3. Dementia Caregiving in the US. Caregiving.org. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Dementia-Caregiving-Report-2017_Research-Recommendations_FINAL.pdf. Published October 2017. Accessed November 30, 2020.

4. Garrison LP Jr, Baumgart M, El-Hayek YH, Holzapfel D, Leibman C. Defining elements of value in Alzheimer’s disease. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2021;7(1S):S7-S11.

5. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. The QALY: rewarding the care that most improves patients’ lives. December 2018. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/QALY_evLYG_FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2021.

6. Basu A, Carlson J, Veenstra D. Health years in total: a new health objective function for cost-effectiveness analysis. Value Health. 2020;23(1):96-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.10.014

7. Women and Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/women-and-alzheimer-s. Accessed December 28, 2020.

8. Super N, Ahuja R, Proff K. Reducing the Cost and Risk of Dementia Recommendations to Improve Brain Health and Decrease Disparities. https://milkeninstitute.org/reports/reducing-cost-and-risk-dementia. Published 2019. Accessed December 28, 2020.

9. Aranda MP, Vega WA, Richardson JR, Jason Resendez. Priorities for Optimizing Brain Health Interventions Across the Life Course in Socially Disadvantaged Groups. 2019. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/fiu_paper_10.18.19%20%281%29.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2020.

10. Gaskin DJ, LaVeist TA, Richard P. The Costs of Alzheimer’s and Other Dementia for African Americans. 2013. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/sites/default/files/USA2_AAN_CostsReport.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2020.

11. Gaskin DJ, LaVeist TA, Richard P. Latinos and Alzheimer’s Disease: New Numbers Behind the Crisis. 2016. https://roybal.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Latinos-and-AD_USC_UsA2-Impact-Report.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2020.

12. Cookson R, Griffin S, Norheim OF, Culyer AJ. Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Quantifying Health Equity Impacts and Trade-Offs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021.

13. Griffin S, Love-Koh J, Pennington B, Owen L. Evaluation of intervention impact on health inequality for resource allocation. Med Decis Making. 2019;39(3):171-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X19829726

14. Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine (review) and Memantine for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (amended). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta111/documents/final-guidance-ta1112. Published November 2006. Accessed November 30, 2020.

15. Marsh K, Lanitis T, Neasham D, Orfanos P, Caro J. Assessing the value of healthcare interventions using multi-criteria decision analysis: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(4):345-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0135-0

16. Hansen P, Devlin N. Multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) in healthcare decision-making. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-98. Published April 26, 2019. Accessed November 30, 2020.

17. Barbarino P, Gustavsson A, Neumann PJ. Long-term value demonstration in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence needs. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2021;7(1S):S18-S23.