Defining Elements of Value in Alzheimer’s Disease

Louis P. Garrison, Jr, PhD, Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Matthew Baumgart, Vice President, Health Policy, Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, IL, USA; Youssef H. El-Hayek, PhD, MBA, Senior Consultant, Shift Health, Toronto, Ontario Canada; Drew Holzapfel, MBA, Executive Director, The Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease, Washington, DC, USA; Chris Leibman, PharmD, MS, Senior Vice President, Value and Access, Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA

The Importance of Value Assessment in Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease presents one of the greatest health, economic, and societal challenges of our time. The global community has now reached a critical point in our response to this challenge, as decades of scientific research will likely soon deliver the first disease-modifying Alzheimer’s therapies. This inflection point generates an urgent need for greater discussion and consensus on how to assess the full value of new Alzheimer’s therapies. This discussion, and the resulting decisions by value assessors, policy makers, and other stakeholders, will play a fundamental role in shaping long-term responses to Alzheimer’s disease in countries around the world.

The stakes are high. Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are grave and growing threats with dramatic impacts on people, families, communities, economies, and societies around the world. Prevalence is projected to roughly triple from more than 50 million in 2019 to around 152 million by 2050.1 This growing prevalence also brings immense rising costs, currently estimated at $1 trillion and projected to double by 2030.1 Yet even this dramatic figure may actually understate the societal and economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease, given its complex impacts and hidden costs.

"Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are grave and growing threats with dramatic impacts on people, families, communities, economies, and societies around the world."

Against this backdrop, new disease-modifying Alzheimer’s therapies offer the potential to change the course of both individual patient’s disease progression and the global Alzheimer’s crisis. While therapeutic progress has been slow in recent decades, there are now currently 29 candidates in phase III clinical development.2 Further, 80% of all candidates (across all phases of development) are disease-modifying therapies, representing a potential step-change to treatment.2 New disease-modifying therapies may finally be available to those with Alzheimer’s disease in the next several years.

Value assessments and decisions will shape the real-world impact of these therapies. Therefore, now is the time for value assessors, policy makers, the medical and advocacy communities, the private sector, and other key stakeholders to engage in greater dialogue about how the value of a treatment can best reflect the full scale of the Alzheimer’s challenge.

While traditional value frameworks provide an important starting point, Alzheimer’s disease presents a uniquely complex and widespread burden—and resulting potential for therapeutic value—that is not fully captured by current frameworks. This is a progressive disease that grows worse over many years; places an immense strain on caregivers’ and families’ health, finances, and productivity; and generates a number of direct and indirect costs for health and long-term care systems, economies, and society. However, traditional value frameworks do not fully capture these considerations.

To advance the Alzheimer’s value dialogue, this article provides an overview of forward-looking approaches and diverse perspectives from academia, policy and advocacy experts, and industry. It adds to the value discussion by examining several key topics:

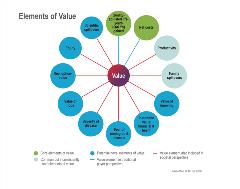

• Considerations beyond cost per QALY (quality-adjusted life years) and the novel elements of value in the ISPOR value flower (Figure 1)

• Patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on the real-world outcomes that are most meaningful to them

• The “hidden” costs of Alzheimer’s disease for patients, caregivers, families, health systems, economies, and society overall

• How recent research findings and the need for continuous innovation can inform value discussions and decisions.

We hope the article sparks greater discussion of value in Alzheimer’s, including the full range of costs and impacts from the disease, the lived experience of patients and caregivers, and the cutting edge of medical science. Ultimately, this more nuanced perspective can help to ensure key value decisions are aligned with the urgency of the Alzheimer’s challenge and the needs of those most directly affected.

The Value Flower: Extending the Value Paradigm

Alzheimer’s disease presents challenges to typical cost-effectiveness frameworks, which for decades have centered on QALYs and net cost. QALYs assess a treatment’s benefits based on the narrow criteria of length of life and quality of life, while net cost considers the treatment’s direct medical costs and the healthcare savings it provides. Together, these 2 elements lead to cost per QALY, which serves as a flexible and convenient metric for measuring and comparing health outcomes across diverse diseases and treatment.

However, in recent years, there has been significant concern about whether the cost per QALY model is appropriately suited to certain disease areas, including Alzheimer’s. This framework includes paid patient costs and benefits but omits a range of opportunity costs. Further, in Alzheimer’s disease, the patient typically becomes dependent on the caregiver for their everyday functioning, which makes the burden on the caregiver an essential aspect of the disease. However, this burden is currently excluded from traditional cost-effectiveness frameworks, which also do not fully capture the burdens on families, economies, and society.

Figure 1. Elements of value in the value flower.

Given these gaps, it may be necessary to expand the cost per QALY framework to include new elements of burden and value, or to develop a novel framework that is better suited to these dynamics. In 2018, an ISPOR task force group reviewed a number of alternative frameworks and synthesized an overarching approach, often referred to as the value flower.3 The value flower “broadens the view of what constitutes value in healthcare” with 10 elements that extend beyond traditional cost per QALY analysis (Figure 1). Several of these elements of value are especially relevant to Alzheimer’s disease.

"In Alzheimer’s disease, the patient typically becomes dependent on the caregiver for their everyday functioning, which makes the burden on the caregiver an essential aspect of the disease."

Productivity measures the impact on patients’ and caregivers’ ability to work, both at home and in the labor market. As caregivers often work less or drop out of the workforce altogether, lost productivity adds to the total costs of the disease. This results in an immense financial and economic burden on caregivers, families, and societies, yet the potential value of reducing these impacts is not included in the traditional cost per QALY approach.

The concept of “scientific spillover” measures the value of scientific research that advances the overall field, regardless of direct resulting health benefit. For example, basic science or clinical trial results may not lead to an approved therapy that directly benefits patients, but they can contribute to the overall body of knowledge in Alzheimer’s disease.

“Family spillovers” measures the “disutility” (ie, harmful physical and mental effects of Alzheimer’s disease) on caregivers and family over a period of time. This is especially relevant given research that finds caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients face greater health impacts and higher healthcare costs.4

A number of the value flower’s elements focus on the value of reducing uncertainty. The “value of knowing” measures the benefits of being more certain about the patients for which a specific treatment or intervention will be effective (eg, a blood test). The “insurance value” measures the value of increasing people’s financial protection from the costs of Alzheimer’s. “Fear of contagion” measures the value of reducing people’s fear of developing Alzheimer’s disease and having no effective treatment options.

“Distributional equity” measures the value of addressing the disproportionate impacts of Alzheimer’s disease on different groups and communities, including based on gender, racial and ethnic identity, socioeconomic status, and educational level. It could also include the value of greater equity between people who develop Alzheimer’s and those who do not develop it. This element of value is explored in greater detail in the article by Basu et al in this supplement.5

While further work is needed to determine which of these elements are most important in Alzheimer’s disease and how they can be measured, the value flower provides a core framework to consider how a potential Alzheimer’s therapy can benefit patients, caregivers, and society overall, especially beyond traditional cost per QALY.

The Perspective of Patients and Caregivers: Defining Meaningful Real-World Outcomes

Recent research has attempted to better understand the real-world needs and priorities of those most directly affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Together with the value flower, this research provides the basis for a broader range of value considerations—grounded in meaningful outcomes for patients and caregivers.

A systematic review, conducted on behalf of the Real-World Outcomes Across the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum: A Multimodal Data Access Platform (ROADMAP) initiative, examined 34 relevant studies to better understand the priorities of Alzheimer’s patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers in countries around the world. The review found patients and caregivers value a range of key priorities that are not typically included in clinical trials or value discussions, such as independence and identity.6 Notably, these priorities are consistent across different studies, geographies, and patients and caregivers.

"As the primary beneficiaries of new Alzheimer’s therapies, patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives must ground decisions about value."

Of the 34 studies included in the systematic review, the most frequently reported important outcomes included maintaining a

patient’s independence, including both physical and psychological autonomy; mental health impacts, such as anxiety and depression,

with spousal caregivers noting that targeting depression is critical; and the ability of patients to maintain their identity, including knowledge, personality traits, and emotional bonds.

Overall, this research finds that those most directly affected by Alzheimer’s disease are primarily concerned with observable effects on their daily life. Therefore, a therapy’s ability to mitigate or delay the negative impacts of Alzheimer’s on these areas is its greatest source of value in the view of patients and caregivers—more so than the raw clinical measurement of biomarkers or an abstract cognitive test score. While these measures can serve as important proxies, patients and caregivers are ultimately focused on the impacts for how they feel, live, interact, and see themselves every day.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Patient and Caregiver Engagement (AD PACE) What Matters Most (WMM) study provides further evidence to support these findings. The WMM study conducted qualitative interviews with patients and caregivers across 5 groups, from individuals with higher risk or underlying pathology but no symptoms to caregivers of those with severe Alzheimer’s disease.7

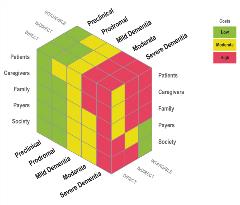

Figure 2. The hidden costs of Alzheimer's disease.

Of 42 concepts whose importance was assessed by the WMM study, all were rated by at least half of patients as very important or extremely important, indicating that those living with dementia have a broad and diverse set of priorities and concerns. Caregivers had a narrower set of concepts they considered important, but both agreed on the importance of concepts linked to emotional well-being, such as not feeling down and depressed, not feeling anxious, and having a sense of purpose. These were rated as more important than more “practical” concepts like remembering people’s names or learning new information and tasks.

As the primary beneficiaries of new Alzheimer’s therapies, the patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives must ground decisions about value. Initial research reveals a broad set of everyday priorities, many of which are not currently integrated into traditional value frameworks. Further work is needed to determine how best to measure these priorities in a way that is consistent and easy to incorporate when assessing value for specific therapies.

Financial, Economic, and Societal Burden: Examining the “Hidden Costs” of Alzheimer’s

Due to its impacts on patients and caregivers, Alzheimer’s disease leads to cascading costs for both those directly affected and society more broadly. Dementia is generally recognized as one of the most expensive health challenges of our time, generating roughly $1 trillion in costs (or greater than 1% of global gross domestic product [GDP]).8,9

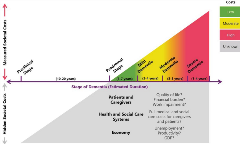

However, given the nature of the disease, these costs can be hidden (ie, spread across health systems, long-term care systems, and payers; paid by families out of pocket; attributed to comorbid conditions, etc), creating an invisible drain on the workforce and beginning even before diagnosis (Figure 2).10

“Tip of the Iceberg: Assessing the Global Socioeconomic Costs of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and Strategic Implications for Stakeholders” by El-Hayek et al provides the framework for a more comprehensive analysis of these costs, which could help to better align the value of therapies with the true burden of Alzheimer’s disease and the potential savings of new therapies. The piece finds that the frequently measured costs of Alzheimer’s are only the “tip of the iceberg,” missing both certain types of costs (eg, out-of-pocket, lost productivity, etc) as well as a certain time (eg, costs that occur before diagnosis) (Figure 3).10

Figure 3. The costs of dementia steadily increase, beginning before diagnosis.

The authors outline the costs of Alzheimer’s disease in 3 categories: (1) direct costs, (2) indirect costs, and (3) intangible costs. Direct costs include medical costs such as medication and hospitalization, along with social or elder care costs such as long-term residential care. Direct costs begin even before Alzheimer’s diagnosis and steadily increase over time. They include out-of-pocket spending, which is high relative to the spending of those without the disease and “disproportionately borne by women and minorities.” Hidden direct costs may also include the higher costs of comorbidities for Alzheimer’s patients and caregivers.

Indirect costs constitute a less visible but similarly heavy burden. These include the cost of uncompensated caregiving, nearly $244 billion in the United States in 2019.11 These also include productivity losses, as well as the financial impact on caregivers’ income and savings. Indirect costs may also accrue for years prior to a diagnosis, yet they also increase during the Alzheimer’s journey as the disease reduces patients’ autonomy and self-sufficiency.

Finally, intangible costs are those that burden patients and family members in ways that are difficult to measure in financial terms. These types of costs include the reduced quality of life experienced by people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers.

Given these considerations, the research community needs additional consensus, tools, and data to measure and understand the full real-world costs of Alzheimer’s disease. For example, new technology, such as apps or wearables, could possibly measure time spent on caregiving, and new biomarker tests could enable earlier diagnoses and thus detect changes and costs earlier in disease progression. Value assessment can also benefit from observational studies and registries that measure disease-related burdens “across the continuum of aging, cognitive impairment, and dementia.”

The Value of Innovation: Evolving Value Assessment to Reflect the Current State of Alzheimer’s Science

In addition to the considerations above, determining the value of Alzheimer’s therapies must evolve to reflect the latest science on Alzheimer’s disease. In the past 2 decades, researchers, the medical community, and the private sector have achieved important strides to better understand Alzheimer’s disease and develop new interventions. This is a journey of progress, enabling the scientific community to possess a deeper understanding of Alzheimer’s, how to identify and target the disease in its earliest stages, and how to account for its heterogeneity. With a record 29 drug candidates in phase III clinical development—59% of which are disease-modifying therapies—the future now looks brighter than ever.2

However, since therapeutic progress has been slow, value assessors and payers have not kept pace with the latest scientific findings. As a result, it is now time to update value frameworks to reflect the cutting edge of Alzheimer’s science and innovation. This alignment offers the greatest opportunity to ensure the right patients receive the right therapies at the right time to achieve the best outcomes.

Several key findings are essential. Early detection, diagnosis, and intervention are critical to both preserve the real-world outcomes that matter to patients and bend the long-term cost curve for society. A given therapy will likely achieve the greatest value in patients in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s or with mild cognitive impairment. Value frameworks should reflect these considerations, ensuring that the right patients can receive a therapy early enough to maximize its benefits, savings, and overall value.

Researchers now also have a greater understanding of how Alzheimer’s disease ripples across society. These impacts and costs are not captured in one “budget,” but spread across households, health systems, long-term care systems, payers, communities, economies, and more. Together, these costs represent one of the most expensive healthcare challenges in our world, and this should be reflected in valuing new therapies.

Finally, new therapies will likely change the dynamics of how Alzheimer’s disease is detected, diagnosed, and discussed, while also stimulating new innovation. Any successful therapy will affect all other innovation efforts, driving further progress; others can learn from and build upon a breakthrough. Therefore, value frameworks must continuously evolve to capture and reflect these changes.

New Directions in Value Assessment for Alzheimer’s Disease

There is clear and urgent need for innovative approaches that more accurately and appropriately evaluate the full benefits and savings of new therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Though the area is ripe for further research, existing scholarship offers several primary takeaways:

• The unique nature, challenges, and impacts of Alzheimer’s disease require expanding the value discussion beyond traditional cost per QALY, incorporating additional considerations or turning to novel frameworks like the value flower.

• Patients and caregivers prioritize meaningful, but sometimes intangible real-world outcomes, such as the preservation of independence, emotional well-being, and identity.

• The costs of Alzheimer’s disease are hidden across multiple systems and stakeholders, and they begin to accrue years before diagnosis.

• Maximizing the value of new therapies likely requires intervening early in disease progression and identifying the right subpopulations of patients.

• Value assessment in Alzheimer’s disease can evolve to reflect new scientific findings and innovations, and then continue to evolve in the future.

The next 2 articles in this supplement provide additional detail about these and other aspects of value in Alzheimer’s disease.5,12 We look forward to engaging the Alzheimer’s community, value assessors, and policy makers in further discussions about how to integrate these considerations into value decisions and ultimately accelerate our world’s response to Alzheimer’s disease. •

References

1. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed November 24, 2020.

2. Cummings J, Lee G, Ritter A, Sabbagh M, Zhong K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2020. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2020;6(1):e12050. doi:10.1002/trc2.12050

3. Lakdawalla DN, Doshi JA, Garrison LP Jr, Phelps CE, Basu A, Danzon PM. Defining elements of value in health care—a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force Report [3]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):131-139. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.007. PMID: 29477390.

4. Wong W. Economic burden of Alzheimer disease and managed care considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(8 Suppl):S177-S183. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.88482. PMID: 32840331.

5. Basu A, Lynn N, Peschin S, Resendez J. Value assessment in Alzheimer’s disease: a focus on equity. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2021;7(1S):S12-S17.

6. Tochel C, Smith M, Baldwin H, et al. What outcomes are important to patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, their caregivers, and health-care professionals? A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2019;11:231-247. doi:10.1016/j.dadm.2018.12.003

7. New UsAgainstAlzheimer’s Research Shows What Matters Most to Patients and Caregivers in Drug Treatments. UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/press/new-usagainstalzheimers-research-shows-what-matters-most-patients-and-caregivers-drug. Published July 29, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2020.

8. Alz.co.uk. 2019. World Alzheimer Report 2019 [online]. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2020.

9. GDP (current US$). Data World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD. Accessed November 24, 2020.

10. El-Hayek YH, Wiley RE, Khoury CP, et al. Tip of the iceberg: assessing the global socioeconomic costs of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and strategic implications for stakeholders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(2):323-341. doi:10.3233/JAD-190426.

11. 2020 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s and dementia. 2020;16(31):391-460. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12068.

12. Barbarino P, Gustavsson A, Neumann PJ. Long-term value demonstration in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence needs. Value & Outcomes Spotlight. 2021;7(1S):S18-S23.