Integrating Artificial Intelligence Into Systematic Literature Reviews: A Review of Health Technology Assessment Guidelines and Recommendations

Yifei Liu, BSc, formerly Roche, Welwyn, United Kingdom; Seye Abogunrin, MD, MPH, MSc; Clarissa Emy Higuchi Zerbini, BSc, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland

Introduction

Systematic literature reviews (SLRs), a critical part of health technology assessments (HTAs), are often used to systematically evaluate the efficacy, safety, and effectiveness of health interventions. However, the SLR process remains highly labor-intensive and time-consuming. It involves a sequence of interdependent steps, starting with the formulation of the research question and development of a review protocol, followed by the design and execution of a comprehensive search strategy, screening of titles and abstracts, full-text assessment, manual data extraction and validation, risk of bias assessment, and finally, evidence synthesis. Among these, tasks such as screening large volumes of records and manually extracting data are particularly resource-heavy and contribute significantly to the overall time burden. Due to this complexity, completing an SLR typically requires the sustained effort of 5 reviewers and takes, on average, over 67 weeks to complete.1 Moreover, SLRs often struggle to keep up with the rapid influx of new evidence, requiring frequent updates and repetition of the lengthy process. These challenges can increase the workload and complexity of preparing HTA submissions, potentially contributing to delays in evaluations.

With rapid development of artificial intelligence, there is great potential to streamline and automate many tasks within the systematic literature review process.

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI), there is great potential to streamline and automate many tasks within the SLR process. For example, AI tools such as Rayyan, DistillerSR, and EPPI Reviewer can facilitate study screening by predicting the relevance of unscreened records, while tools like RobotReviewer and SWIFT-Review can be used to automate data extraction.2 By incorporating these AI technologies into the current SLR workflow, the overall efficiency can be greatly improved. This could ultimately accelerate the SLR process, and consequently, HTA dossier preparation, potentially supporting timelier HTA submissions.

However, it remains unclear whether HTA agencies endorse or recommend the use of AI tools in SLRs. Therefore, this study aims to review and summarize the current HTA guidelines regarding the use of AI in conducting SLRs.

Methods

We manually searched the websites of 54 HTA agencies, including all 53 members of the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment3 and the European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA), for manuals or guidelines on SLRs and reviewed them for relevant AI-related guidance. Additionally, we reviewed guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions,4 the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care,5 and the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis,6 given their influence on HTA guideline development. No AI technologies were used in the conduct of this study.

Results

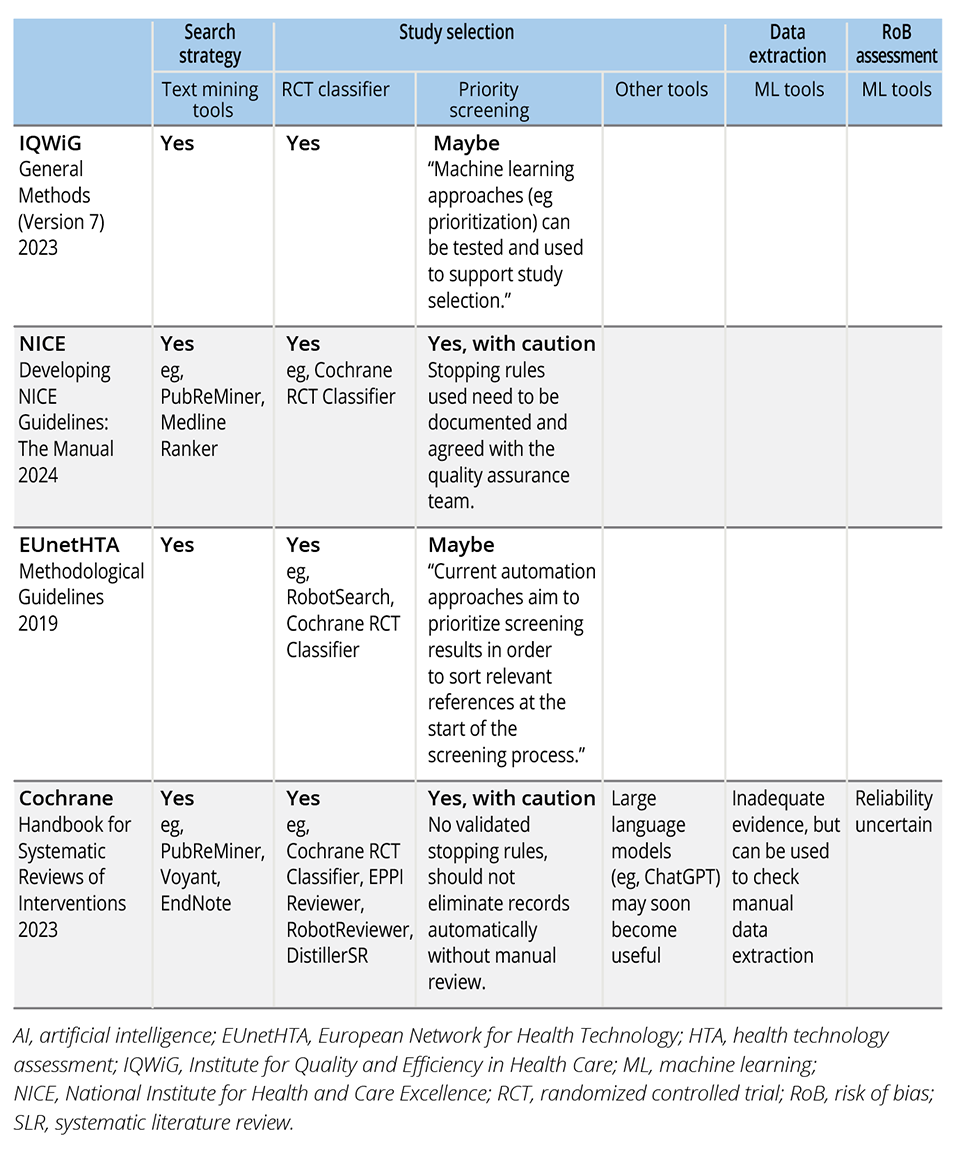

Out of the 54 HTA agencies reviewed, we found guidelines or recommendations from 3 agencies—Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and EUnetHTA—relevant to the use of AI in conducting SLRs. For IQWiG, information was sourced from the General Methods document.7 As for NICE, while the Health Technology Evaluations Manual8 did not include information about the use of AI in SLR, relevant guidance was found in the Developing NICE Guidelines Manual.9 EUnetHTA’s guidelines were drawn from the Methodological Guidelines - Process of Information Retrieval for Systematic Reviews and Health Technology Assessments on Clinical Effectiveness.10 Among the 3 SLR handbooks, only the Cochrane Handbook included relevant guidance on AI tools. A summary of these guidelines can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of HTA guidelines on the use of AI in SLRs.

Literature Search

IQWiG, NICE, EUnetHTA, and the Cochrane Handbook all recommend the use of text-mining and frequency analysis tools to develop more effective and comprehensive search strategies. These tools can be used to identify important keywords, synonyms, and subject headings from previously identified relevant articles. Specific tools recommended include PubReMiner, Medline Ranker, searchbuildR, Voyant, and EndNote.

Study selection

For study selection, 2 main types of AI tools are recommended: randomized controlled trial (RCT) classifiers and priority screening tools. RCT classifiers are machine learning (ML) tools trained to predict the likelihood of a record being an RCT, while priority screening tools predict the relevance of unscreened records based on a training set or prior decisions by human reviewers and re-rank the records from most to least relevant.

All 4 organizations support the use of validated ML classifiers to enhance the efficiency of study selection, though with caution. NICE, for example, stresses the importance of ensuring that classifiers are used on appropriate data with known performance characteristics. Currently, these ML classifiers are primarily validated for identifying RCTs, and EUnetHTA explicitly advises against their use for nonrandomized studies. Some of the ML-based RCT classifiers recommended include the Cochrane RCT Classifier, RobotSearch, EPPI-Reviewer, RobotReviewer, and DistillerSR.

Similarly, all 4 organizations recognize priority screening as a valuable tool. However, both NICE and Cochrane point out that when using priority screening, there is currently no validated stopping rule—a predefined criterion that indicates when it is safe to stop manually screening additional records once the likelihood of finding more relevant studies becomes low. As a result, NICE recommends that the specific priority screening method used be documented and agreed upon in advance with the quality assurance team, while the Cochrane Handbook advises against automatically excluding records without manual review.

Additionally, the Cochrane Handbook highlights emerging tools based on large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, which may soon enable automatic study selection without the need for training. However, as of now, there are insufficient evaluations of the performance of these LLMs.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Handbook recognizes the availability of ML tools designed to automate data extraction and risk of bias assessment. However, these tools are currently limited in their ability to extract many of the necessary elements for SLRs, and there is insufficient evidence regarding their performance and reliability. Consequently, no specific tools have been recommended for these purposes. Despite this, Cochrane suggests that these automated or semi-automated approaches can still be utilized as supplementary checks for the manually extracted data.

Conclusions

The findings of this study show that most HTA agencies have not yet provided specific guidelines regarding the use of AI in SLRs, with only a few, including IQWiG, NICE, and EUnetHTA, offering relevant recommendations. Even among those that recognize the potential of AI to improve the efficiency of SLRs, there is a clear sense of caution. None of the agencies advocate for widespread adoption of AI tools, and the guidance emphasizes the importance of using well-validated tools. This cautious approach is likely driven by concerns about the reliability, accuracy, and transparency of AI-based methods.

While artificial intelligence tools hold significant promise for addressing inefficiencies in the systematic literature review process, it is crucial that these efficiency gains do not come at the expense of quality.

While AI tools hold significant promise for addressing inefficiencies in the SLR process, particularly in automating tasks such as screening large volumes of records, it is crucial that these efficiency gains do not come at the expense of quality. Currently, many of the available AI tools are still limited in scope and have not been thoroughly evaluated, making them unsuitable for independent use at this stage.

Nevertheless, AI tools can serve as valuable assistants in the current SLR workflow rather than replacing human reviewers entirely. For instance, priority screening algorithms could be leveraged to identify the most relevant records earlier in the screening process. Moreover, AI-driven data extraction can act as a check against manually extracted data, helping to identify potential errors or omissions. In some cases, AI tools could potentially replace 1 human reviewer, reducing the labor intensity. However, this approach might be more controversial as it challenges the current best practice of involving 2 independent human reviewers.4

There is a clear need for further evaluations to assess the performance and reliability of AI tools in SLRs. Comprehensive studies are required to evaluate their accuracy across different datasets and study types. As more evidence becomes available, HTA agencies will be better equipped to update their guidelines and offer more definitive recommendations on the use of AI in SLRs. Until then, a cautious and balanced approach—using AI tools to assist but not replace human input—remains essential to ensure both efficiency and quality in SLRs for HTA.

Implications to Key Stakeholders

Researchers and review authors: AI tools can enhance the efficiency of SLRs, but researchers should use them as supportive tools rather than replacements for human reviewers. It is essential to select AI tools based on their validated performance characteristics.

HTA agencies: Many HTA agencies have yet to provide specific guidelines for the use of AI in SLRs and the extent of documentation required for any AI tools that are used. Updating their guidelines to reflect the current state of AI technologies would offer clearer direction on how to effectively and safely integrate AI into the HTA process.

References

- Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012545. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012545

- Blaizot A, Veettil SK, Saidoung P, et al. Using artificial intelligence methods for systematic review in health sciences: a systematic review. Research Synthesis Methods. 2022;13(3):353-362. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1553

- INAHTA Members List. INAHTA. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.inahta.org/members/members_list/

- Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4. Cochrane. Updated August 22, 2024. Accessed July 15, 2024. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York Associates International. Published January 2009. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

- Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. Published March 2024. Accessed July 15, 2024. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- IQWiG. General Methods - Version 7.0. Published September 19, 2023. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.iqwig.de/methoden/general-methods_version-7-0.pdf

- NICE. NICE Health Technology Evaluations: The Manual. NICE. Published January 31, 2022. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36

- NICE. Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual. NICE. Published October 31, 2013. Updated May 29, 2024. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20

- EUnetHTA JA3WP6B2-2 Authoring Team. Process of Information Retrieval for Systematic Reviews and Health Technology Assessments on Clinical Effectiveness (Version 2.0). Accessed July 17, 2024. https://www.eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/EUnetHTA_Guideline_Information_Retrieval_v2-0.pdf

a IQWiG: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care.

b NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

c EUnetHTA: European Network for Health Technology.