From Shopping for Utilities to Investing in Societal Impact: Realizing the Promise of a Broader Value Definition in Economic Evaluation

Ahmed Seddik, PhD, MSc, BDS, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands

Recent efforts to standardize measuring the societal impact of medicines have been mounting, yet the application of the societal perspective in routine health economic evaluations remains limited. This article explores potential foundational barriers in HEOR that limit the uptake of proposed forward-looking frameworks and ways to accelerate this. Drawing from my doctoral research at the University of Groningen,1 this article builds on a growing body of evidence that calls for the integration of societal impact into health economic evaluations.

“Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will; and, in our corporate capacity, we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (1762).2

In recent decades, societal priorities (or the general will, as Rousseau puts it) have been slowly shifting. Issues like climate change, sustainability, and equity are driving demand for long-term planning across industries, including healthcare. Rousseau’s philosophy reminds us that societal progress requires collective action and decision making aligned with the broader good. In healthcare, this means expanding health technology assessment (HTA) frameworks to reflect societal benefits like workforce productivity, economic, and fiscal impacts—elements that traditional models often overlook. Advances in data availability, statistical tools, and computational power have made it possible to evaluate such complex, long-term impacts. Yet, current decision-making frameworks often remain unaligned with society’s broader expectations. This often creates a dissonance between payer priorities and societal needs.

As an example, consider the rise of gene therapies, which promise transformative outcomes for rare diseases but come with high upfront costs. A narrow payer perspective may focus on immediate expenses, whereas a societal perspective considers the long-term benefits of reduced lifetime healthcare needs and improved quality of life with its broader implications socioeconomically. Such clear disconnect between the payer and societal perspectives highlights an urgency for reframing decision-making frameworks in a way that better aligns with societal goals.

Another quite contrasting example can be drawn from the debate around vaccine funding during a pandemic. Traditional frameworks evaluate vaccines based on direct health benefits and costs saved in treating infections. However, adopting a societal perspective reveals additional value: vaccines reduce workforce absenteeism, stabilize economies, and even foster public trust in health systems. These long-term societal benefits often remain underexplored in short-term models, which reinforces the need for a broader approach.

Current health technology assessment practices are falling short of adopting the societal perspective: Very few guidelines recommend the inclusion of broader value elements.

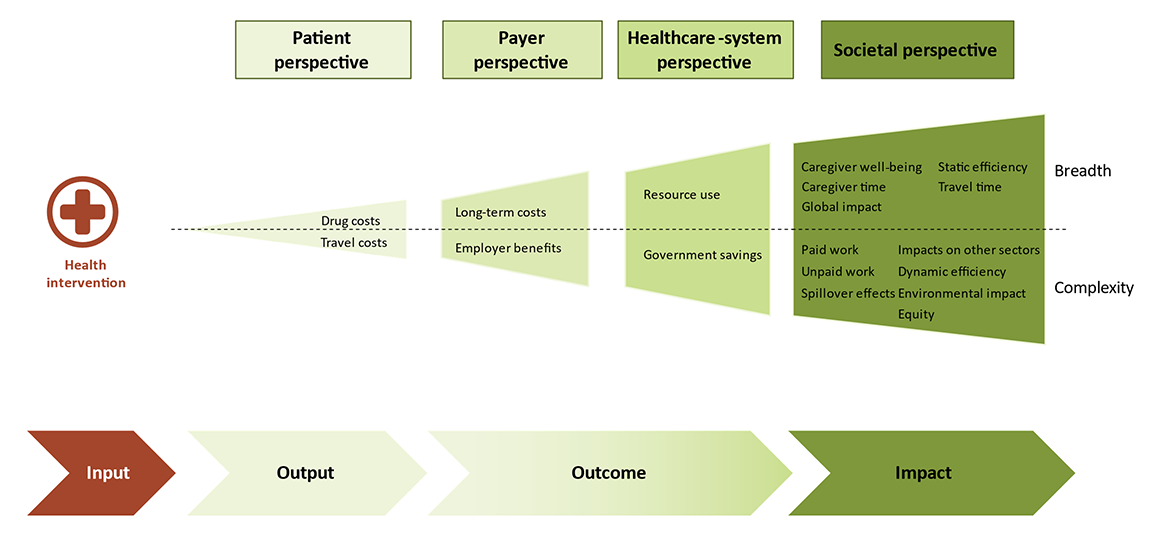

As shown in Figure 1, broadening the perspective of analysis entails considering further elements of value. To that end, research and discussions around this topic have been mounting in recent years, resulting in a growing interest from HTA bodies to recognize the importance of considering societal and novel value elements in economic evaluations. However, it has also been shown that current HTA practices are falling short of adopting the societal perspective: Where many national HTA bodies mention broader value elements in their guidelines, very few of those guidelines effectively recommend the inclusion of these elements as the reference case of model analyses. Furthermore, except for the Netherlands’ HTA body (ZIN) recommending the application of iPCQ questionnaire to capture paid and unpaid work benefits, no other HTA guideline document worldwide currently recommends an explicit approach to measuring broader societal benefits of healthcare innovations.3-6

Figure 1. Current perspectives in pricing and reimbursement decision making are limited to measuring outcomes, those that can be mapped to the payer and healthcare system perspectives. Reflecting the societal preferences in decision making requires broader frameworks that enable the measurement of impacts.

Studies attribute this hesitancy of HTA bodies to adopt and recommend evaluation frameworks that incorporate elements of societal value to various factors, including the narrow remits of payers’ decision making, the feasibility of conducting such analyses, and the lack of local expertise to build broader models.

It is argued here that one important foundational barrier in health economics needs to be further explored and tackled for broadening the definition of value to come to true effect: While weighing patient outcomes against total costs (ie, cost-effectiveness) has proven useful in many instances, it is perhaps time to re-evaluate the maxim that underpins this premise.

The Impact-Maximization Paradigm

Revisiting cost-effectiveness through an impact-maximization view requires rethinking traditional evaluation methods. Cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) aim to maximize utility by measuring and weighing incremental costs against incremental patient utility, typically measured in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). This consumer economics–inspired framework places payers in the role of “shoppers for utilities” in the healthcare marketplace, focusing on maximizing efficiency within limited budgets.

However, healthcare interventions, unlike consumer goods, are meant to generate broader societal benefits beyond the individual, patient-level utility. Analyses adopting the societal perspective consistently reveal higher cost savings and greater long-term impacts. A useful analogy from the world of physics can offer some clarity. In this analogy, traditional (narrow-scope) health economics can be likened to classical physics—effective at explaining the middle ground but inadequate when addressing extremes. Just as classical physics struggles to explain the vastness of the cosmos (astrophysics) or the peculiarities of subatomic particles (quantum physics), so too does classical health economics with the examples given earlier. It struggles with the extra-large—vaccines and public health interventions—and the extra-small, like gene therapies for rare diseases. These outliers require a paradigm shift to frameworks that can address complexity, scale, and long-term societal impacts comprehensively, all under one umbrella and within a standardized set of tools.

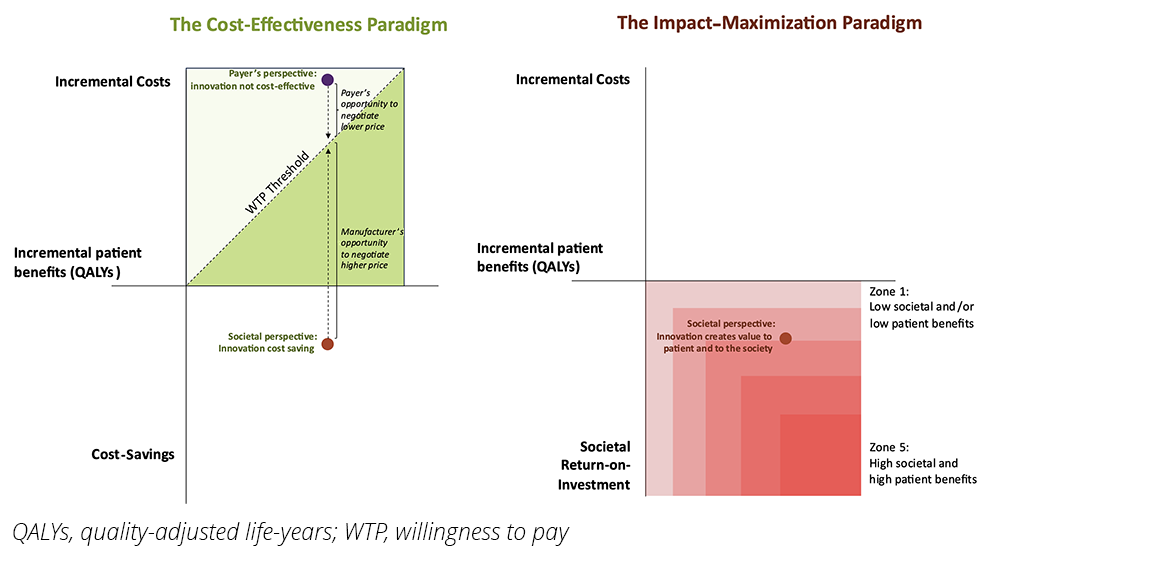

Figure 2 illustrates this paradigm shift with a reimagined cost-effectiveness plane. In traditional CEAs, interventions are judged based on their position in the northeastern quadrant, balancing incremental costs with incremental QALYs, where an innovation’s price is determined by willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds. This method for price determination is useful to payers, provided that narrower perspectives are adopted. On the other hand, models adopting societal perspectives while aiming to determine drug prices by the WTP thresholds present manufacturers with leverage to negotiate higher prices for their innovations. To the detriment of evolving societal preferences, this paradigm where the societal perspective has proven advantageous to manufacturers risks leaving payers reluctant to engage in discussions around broadening the definition of value in healthcare.

Figure 2. Within a conventional cost-effectiveness paradigm (left side), the societal perspective allows manufacturers to negotiate higher prices. In a rethought impact-maximization paradigm (right side), the societal perspective enables payers to assess and prioritize innovations based on their patient benefit and societal return on investment.

Therefore, an adoption of the societal perspective in health economic evaluations would only make sense if it were combined with a paradigm shift for evaluation, where manufacturers are expected to produce innovations that benefit both patients and society. In this way, a cost-effectiveness analysis of an innovative therapy adopting the societal perspective should aim for the southeastern quadrant, where the intervention seeks to demonstrate an improvement in incremental QALYs alongside maximized long-term societal impacts.

Healthcare interventions, unlike consumer goods, are meant to generate broader societal benefits beyond the individual, patient-level utility.

This visualization reframes the role of payers as strategic investors in societal health. Payers are empowered to demand evidence demonstrating both patient and societal returns on investment. The goal becomes clear: innovative therapies must deliver value for patients while advancing societal objectives, with optimal results falling as far into the southeastern quadrant of a cost-effectiveness plane as possible. According to this paradigm, the price of innovative therapies is determined based on the opportunity cost, not on an exposing and disempowering WTP threshold.

Therefore, it is strongly argued that this shift would have significant implications:

- Empowering Payers: When the societal perspective is coupled with impact maximization as a paradigm for decision making, HTA bodies and payers can gain tools to assess societal return on investment, allowing them to align healthcare investments with long-term societal priorities. This shift reframes payers not as mere “buyers” but as strategic “investors” in societal health.

- Incentivizing Innovation: In this view, manufacturers are encouraged to design therapies that meet multidimensional value expectations. With patient-centricity still in focus, innovation for societal impact comes closer to the foreground. Growing societal priorities for topics such as pandemic preparedness, antimicrobial resistance, rare diseases, and others become more clearly reflected in manufacturers’ innovation agendas.

- Redefining Metrics: In line with current trends for long-termism as a lens for decision making, success becomes no longer limited to efficiency thresholds and evolves to include a broader capacity to drive societal welfare.

This approach enables healthcare decision makers to step beyond transactional buyer-seller dynamics founded on principles of consumer economics, to embrace investment partnerships that deliver long-term societal benefits.

An Opportunity for Pharma: Bridging Stakeholder and Shareholder Interests Through Social Impact

Beyond HTA, societal impact is gaining traction in corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) frameworks. These frameworks, although distinct from HTA, share common goals with HTA practices. Pharmaceutical companies traditionally separate communication pathways for stakeholders (eg, patients, payers, physicians, and patient advocacy groups) and shareholders (eg, investors). This division can often lead to fragmented strategies that fail to capitalize on shared corporate objectives.

To that end, company-wide messaging can aim to utilize and promote the results from social impact studies to address shareholders and stakeholders simultaneously. Monetized social impact is a means that can allow the analyst to conduct cost-benefit analyses assessing a payer’s or investor’s return on investment. In this view, both the shareholder and the stakeholder are parties that are effectively investing in society’s healthcare, each at a different stage and in different context, with the shared objective of maximizing their return on investments. Whether driven by frameworks that prioritize societal preferences (HTA) or ones that call for conscious investment (ESG), stakeholders and shareholders, when operating within a social impact–oriented decision-making paradigm, both seek to maximize the social welfare function.

Conclusion

This article advocates for a transformative shift in health economics along 3 critical pathways:

- Reframing HEOR: The discipline must expand its definition to include long-term impacts, evolving into the science of Health Economics, Outcomes, and Impact Research (HEOIR).

- Adopting the Societal Perspective: Economic evaluations should make the societal perspective their reference case, and HTA bodies should strive to give manufacturers clear guidance on ways to measure the societal elements of value, ensuring decisions reflect broader benefits beyond immediate outcomes.

- Impact-Maximization Decision Making: Hand in hand with the previous points, and as demonstrated in Figure 2, decision-making frameworks should prioritize societal impact, repositioning healthcare spending as a strategic investment rather than a cost.

By embracing these changes, healthcare decision makers, industry leaders, and policymakers can align healthcare investments across various decision-making contexts with societal progress, building a sustainable, inclusive, and impactful ecosystem for all stakeholders.

References

- Seddik A. The Social Impact of Medical Innovations. University of Groningen; 2024. doi:10.33612/diss.1121096942

- Rousseau JJ. The Social Contract. Cranston M, trans. London, UK: Penguin Classics; 1968. Originally published 1762.

- Gerves-Pinquie C, Nanoux H, Borget I, et al. Adopting a societal perspective in health-economic evaluation: a review of 9 HTA methodological guidelines on how to integrate societal costs [abstract HTA24]. Value Health. 2024;27(6,S1):S248. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2024.03.1375

- Breslau RM, Cohen JT, Diaz J, Malcolm B, Neumann PJ. A review of HTA guidelines on societal and novel value elements. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2023;39(1):e31. doi:10.1017/S026646232300017X

- Ministerie van Volksgezondheid W en S. Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare (2024 version). National Health Care Institute. Published January 16, 2024. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/documents/2024/01/16/guideline-for-economic-evaluations-in-healthcare

- Bouwmans C, Krol M, Severens H, Koopmanschap M, Brouwer W, Roijen LH van. The iMTA productivity cost questionnaire. Value Health. 2015;18(6):753-758. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2015.05.009