Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Section Editor: Koen Degeling, PhD

In this installment of Methods Explained, we delve into distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA). Our insights are drawn from a conversation with 2 leading experts: Richard Cookson, PhD, Professor at the Centre for Health Economics, University of York, and Visiting Professor at the National University of Singapore, who pioneered DCEA’s development and adoption; Stacey Kowal, PhD, Senior Director and Head of Public Policy Evidence at Genentech and Past Chair of the ISPOR Special Interest Group on Health Equity Research, who developed the building blocks for DCEA in the United States.

In this installment of Methods Explained, we delve into distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA). Our insights are drawn from a conversation with 2 leading experts: Richard Cookson, PhD, Professor at the Centre for Health Economics, University of York, and Visiting Professor at the National University of Singapore, who pioneered DCEA’s development and adoption; Stacey Kowal, PhD, Senior Director and Head of Public Policy Evidence at Genentech and Past Chair of the ISPOR Special Interest Group on Health Equity Research, who developed the building blocks for DCEA in the United States.

What is DCEA and how is it used?

DCEA is an essential extension to standard cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). Standard CEA focuses on achieving the maximum health gain for a population, but population-based gains may inadvertently increase health inequalities between different social groups. DCEA addresses this limitation by explicitly quantifying equity in the distribution of health outcomes alongside efficiency in terms of overall health outcomes.

When comparing options, DCEA provides quantitative insights into which social groups benefit the most and which benefit the least. Where traditional CEA quantifies total costs and benefits, DCEA additionally measures the distribution of these costs and benefits across social groups. By understanding these consequences, policy makers can take preventive or corrective actions.

DCEA was originally developed to inform policy decisions in public health, such as assessing the impact of implementing a cancer screening program. It also has become increasingly relevant for health technology assessment. Although decision makers have traditionally taken equity issues into account in health technology assessment implicitly, DCEA helps to solidify this by explicitly calculating health inequality impacts using standardized methods that allow comparisons between different decisions.

How DCEA works: the conceptual framework

The starting point for a DCEA is a robust, payer-appropriate cost-effectiveness model, which must be adapted to estimate cost-effectiveness outcomes for clearly defined social groups. This requires explicitly modeling inequalities at all steps along the staircase to health inequality impact,1 each of which can shift the ultimate impact in a different direction. These inequalities can include social differences in the eligible population, intervention uptake, long-term health effect, and health opportunity cost.

Quantifying the distributional impact using standardized methods requires 2 critical building blocks: information on baseline health inequality and health inequality aversion.

- Baseline health inequality: This is information on the current health differences between social groups in the country of interest. These data are often readily available from national statistics bureaus (eg, differences in life expectancy and health-related quality of life by area deprivation or ethnicity).

- Health inequality aversion: This refers to the degree to which decision makers and members of the public are willing to forgo total health gains to achieve a more equal distribution of health outcomes. This metric is formalized to quantify the value of decreasing (or increasing) health gaps between social groups.

Crucially, distributional analysis requires a broad general-population perspective rather than a narrow clinical perspective. The aim is to reduce social inequality in health within the general population, not just within one specific group of patients.

DCEA can be performed using standard spreadsheet software, but is often performed using R. The York health equity impact calculator2 was developed using R Shiny as an interactive online tool to perform DCEA.

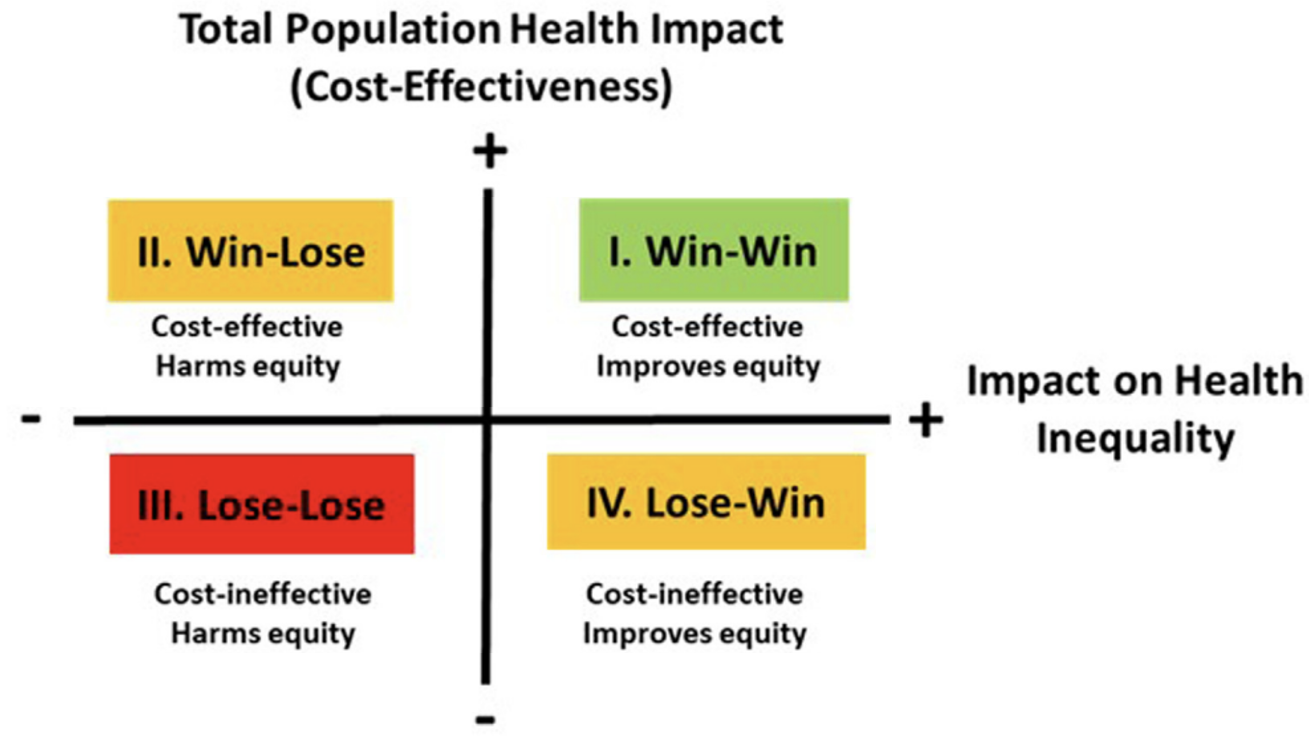

After estimating the breakdown of impacts by social group, the results can be summarized visually in an Equity-Efficiency Impact Plane (Figure). This plane looks like an incremental cost-effectiveness plane but combines costs and effectiveness into a single cost-effectiveness measure on the vertical axis (eg, net health benefit). The impact on health inequality is shown on the horizontal axis. This visual tool allows for easy interpretation:

- Win-Win (northeast quadrant): The intervention is cost-effective and has a positive effect on health inequality.

- Win-Lose (northwest quadrant): The intervention is cost-effective but has a negative effect on health inequality.

- Lose-Win (southeast quadrant): The intervention is not cost-effective but has a positive effect on health inequality.

- Lose-Lose (southwest quadrant): The intervention is not cost-effective and has a negative effect on health inequality.

Figure. Equity-efficiency impact plane combining both the traditional cost-effectiveness outcomes (vertical axis) with the impact on health inequality (horizontal axis)

Are there alternative methods?

The term DCEA is often used as an umbrella term to refer to different methods that incorporate equity considerations. A full DCEA requires redesigning the cost-effectiveness model to estimate outcomes across different social groups. If there is not enough capacity or time to adapt the model, an aggregate or simple DCEA may be performed, which takes aggregate results from a standard CEA and performs some simple distributional calculations on top. This can still allow for inequalities as elements along the staircase to inequality impact to be considered. However, it does not fully capture all elements, may be less accurate than a full DCEA, and will not provide insight into how accounting for social inequalities may alter the standard cost-effectiveness results themselves.

A similar method is extended cost-effectiveness analysis, which is essentially the same but adds further information on the distribution of impacts on household finances as well as impacts on health. This can be especially important in countries without universal health coverage, where out-of-pocket costs can generate substantial financial hardship. There are other ways to incorporate equity considerations into decision making, but DCEA is the only one that is an extension of CEA to explicitly quantify outcomes across groups.

To what extent is it currently being used?

There has been a steep increase in the number of DCEA applications over the past 5 years, in both public health and healthcare.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England and Wales encourages use of DCEA as supplementary analysis both in the development of clinical and public health guidelines and in evaluation of new technologies.3 In the context of technology evaluation, NICE recommends that evidence of substantial health inequality impact be considered alongside an intervention’s cost effectiveness.4 In this context, DCEA can be used as supplementary analysis to measure health inequality impact and assess its magnitude, but use of equity weights to value health inequality impact is discouraged.

Beyond the United Kingdom, China has included DCEA in its guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluation,5 and other countries in the Asia-Pacific region and Latin America are also thinking about including DCEA in decision-making processes.

What is next for DCEA?

To further increase the adaptation and impact of DCEA, development of the methods may focus on 4 key areas:

- Demystification and training: Focusing on simple outcomes and summary graphs will be crucial to helping decision makers understand and use DCEA results.

- Building experience: Building broader experience in applying and reviewing DCEA studies is vital. Performing the first DCEA is a steep learning curve, but subsequent analyses benefit greatly from the experience and gathered data on health gaps.

- Standardization: Building experience will facilitate a certain level of standardization, ideally through establishing a reference case. This would support comparisons across different studies and disease areas.

- Data availability: Greater availability of more granular baseline (income) data linked to health outcomes will be helpful in further increasing the relevance and impact of DCEA.

Key References for Further Reading

A great starting point for a deeper read into health equity considerations in health economics and outcomes research is the primer from the ISPOR Special Interest Group on Health Equity Research, which also provides several insightful case studies.1 For those interested in the comprehensive technical details of DCEA, the textbook by Cookson and colleagues is the go-to resource.6

References

- Griffiths MJS, Cookson R, Avanceña ALV, et al. Primer on health equity research in health economics and outcomes research: an ISPOR Special Interest Group Report. Value Health. 2025;28(1):16-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2024.09.012.

- Love-Koh J, Schneider P, Cookson R. York health equity impact calculator. 2022. University of York. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://shiny.york.ac.uk/dceasimple

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual: NICE process and methods: 7.8 Using economic evidence to formulate guideline recommendations. Published October 31, 2014. Updated October 23, 2025. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/incorporating-economic-evaluation#using-economic-evidence-to-formulate-guideline-recommendations

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Technology evaluation methods support document: health inequalities. 2025. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/consultations/2817/6/distributional-cost-effectiveness-analysis-methods

- Liu G, Hu S, Wu J, et al. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations. Beijing: China Market, 2020.

- Cookson R, Griffin S, Norheim O F, Culyer AJ, eds. Distributional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Quantifying Health Equity Impacts and Trade-Offs. Oxford University Press. 2020.