Access to Multi-Indication Medicines in Underserved Autoimmune Diseases: Are There Better Approaches to Supporting Sustainable Access?

Amanda Whittal, PhD; Jacob Epstein, MEng; Yulia Lazareva, MSc, Dolon Ltd, London, UK; Jens Grueger, PhD, CHOICE Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA; Amanda Cole, PhD, Office of Health Economics, London, UK; Claudio Jommi, MSc, Università del Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy; Pedro Pita Barros, PhD, Nova School of Business and Economics, Carcavelos, Portugal; Lieve Wollaert, MSc; Julien Patris, MSc, argenx, Ghent, Belgium

Introduction

The promise of multi-indication medicines in autoimmune diseases

Autoimmune diseases are a diverse group of conditions in which the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues.1,2 There are approximately 80 to 150 recognized autoimmune conditions, ranging from ultra-rare to more prevalent, affecting an estimated 5% to 10% of the global population.3,4 Many autoimmune diseases are underserved, in that they are rare5 and/or have limited therapeutic options.6 Although such diseases affect relatively small patient populations, their prevalence has been rising steadily.7

There is a high unmet need for new treatment options for these conditions, as current approaches are only available for some autoimmune diseases, and many offer only symptomatic relief or rely on broad immunosuppression.8 Despite this need, innovation has progressed slowly; 50% of all new active substances for autoimmune conditions identified by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) received approval before 2014, and around 16% have been on the market for more than 20 years.9

Recent scientific progress has deepened our understanding of disease pathophysiology, revealing clustering of phenotypically different conditions with similar pathways. For example, the neonatal Fc receptor plays a role in the pathophysiology of several autoimmune diseases, such as generalized myasthenia gravis (MG), Grave’s disease, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).10 Such insights have presented an opportunity for the development of targeted treatments that can deliver therapeutic benefit across a broader range of patients using a single therapeutic agent. However, even with a known mechanism of action and/or safety profile, significant scientific and financial investments are required to prove a therapeutic agent will be safe and effective in a new indication.11-13 Despite the clinical uncertainties and large investment required to bring multi-indication products to patients, there is a growing focus on multi-indication treatments for autoimmune diseases; targeted immunotherapies launched over the past 25 years have had an average of 4 indications per product, with 1 product (adalimumab) being approved for over 10 indications.11

There is a need to explore the challenges for multi-indication medicines in Europe, determine current policies and best practices, and identify actionable solutions to support value-based pricing and sustainable patient access to these medicines.

Despite their promise, multi-indication medicines face significant development challenges from research and development (R&D) and regulatory approval to health technology assessment (HTA), pricing and reimbursement (P&R), and ultimately, patient access and uptake. These challenges are not new. As different cancer types share biological pathways, many oncology drugs target multiple indications (75% as of 202014), yet these treatments have seen mixed success.12 One key issue for multi-indication medicines is that the extent of unmet need and added benefit can vary substantially across diseases.14,15 In a value-based healthcare context, this suggests that prices for such therapies should also vary depending on their use. Forms of indication-based pricing (IBP) have been implemented in some oncology settings, often through a single list price combined with variable per indication discounts that were applied directly or via performance-based agreements.16

Although multi-indication medicines continue to encounter challenges in oncology, 2 disease-specific factors facilitate their adoption, distinguishing this field from immunology. First, patients generally present with a single cancer type, allowing clear attribution of treatment use to a specific indication. Second, outcome measures used for performance-based agreements (eg, survival, progression) are consistent across cancers and correlated with data already captured in claims systems.17

This contrasts with underserved autoimmune diseases, where conditions with disparate phenotypes (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome18,19) often overlap or coexist in the same patient, complicating the attribution of use to a specific indication.20 Outcome measures also vary substantially across autoimmune diseases, limiting the ability to compare value across indications and complicating development of performance-based agreements.21 Moreover, and despite the noted challenges and substantial investment required to prove the safety and efficacy for a new use,13 indication expansion often triggers price erosion of earlier indications in the case of a single price, and the rarity of many underserved autoimmune diseases limits the potential for offsetting this decline through increased volume.14 Evidence from Italy shows that the average additional discount applied with each new indication (on top of discounts for prior indications) is 13%.22 These disease-specific factors are likely to make the challenges already faced by multi-indication medicines in oncology even more pronounced in immunology.

These challenges can hinder development and access of valuable medicines. Without effective solutions, patient access may be limited or delayed due to pricing challenges, payers risk issuing payments that do not reflect a treatment’s value, and manufacturers may lack incentives to develop medicines in additional indications. There is therefore a need to explore the challenges for multi-indication medicines in Europe, determine current policies and best practices, and identify actionable solutions to support value-based pricing and sustainable patient access to multi-indication medicines.

Methodology

Literature review, stakeholder engagement, and framework analysis

A multipronged approach was used in this research. A targeted literature review and case study identification were first conducted to assess European policies, regulations, and best practices for multi-indication medicines. Interviews were then held with former payers and experts from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Spain, with the aim of validating conclusions and discussing country-specific challenges and opportunities.

At ISPOR Europe 2024, a panel was held to disseminate the research findings. A survey was conducted with the audience, which consisted of ~800 stakeholders from industry, academia, and public organizations. The survey enabled participants to provide their perspectives on the key barriers and potential solutions for multi-indication medicines.

The literature review and empirical evidence were then compared against a formal theoretical pricing framework developed by Barros et al.15 The framework analyzes pricing mechanisms and the conditions under which they efficiently align manufacturer incentives with maximizing total therapeutic benefit for patients.15

Results and Discussion

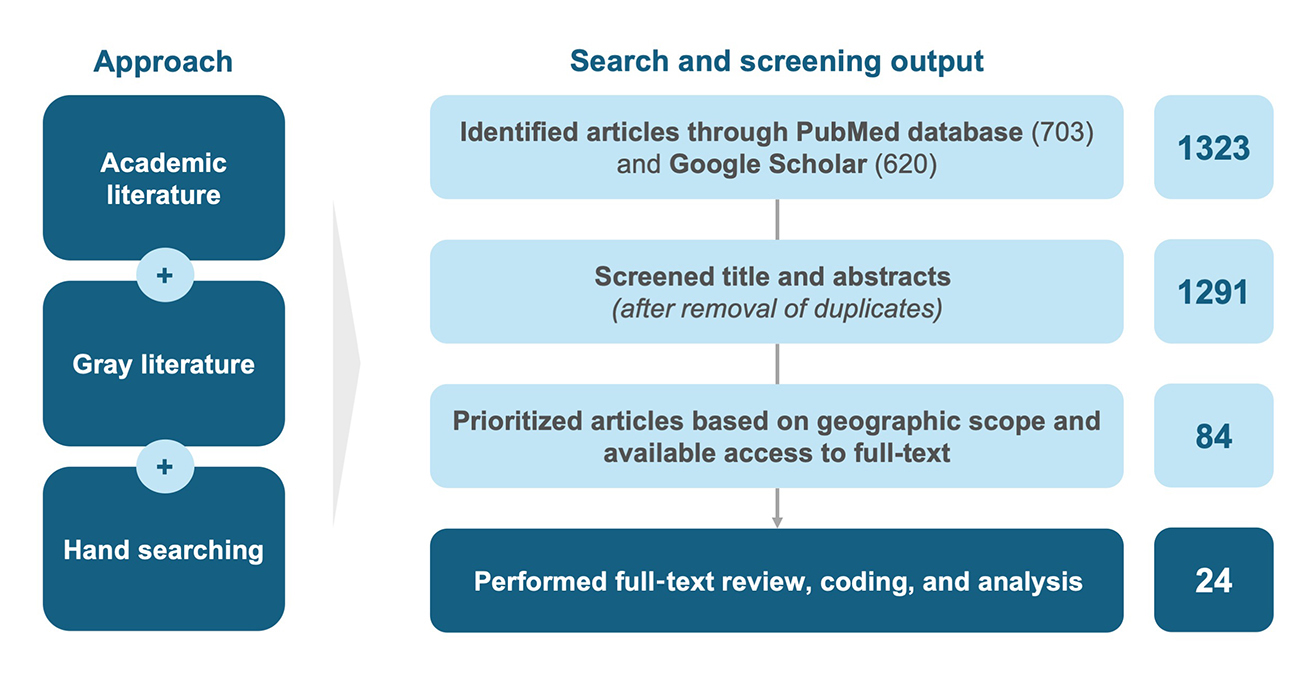

As highlighted in Figure 1, the literature review identified 1323 articles from academic and gray literature. Following title and abstract screening, 84 articles were included for full-text screening, of which 24 were prioritized for full-text review, coding, and analysis, based on content relevance, geographic scope, and full-text availability. Findings revealed a lack of detailed evidence on the broader value of multi-indication products, while the challenges affecting such medicines were widely recognized. The review, together with the expert interviews, provided insight into current and proposed approaches to addressing P&R challenges for multi-indication products in Europe, which are outlined below.

Figure 1. Summary of literature review methodology.

Current P&R approaches for multi-indication medicines

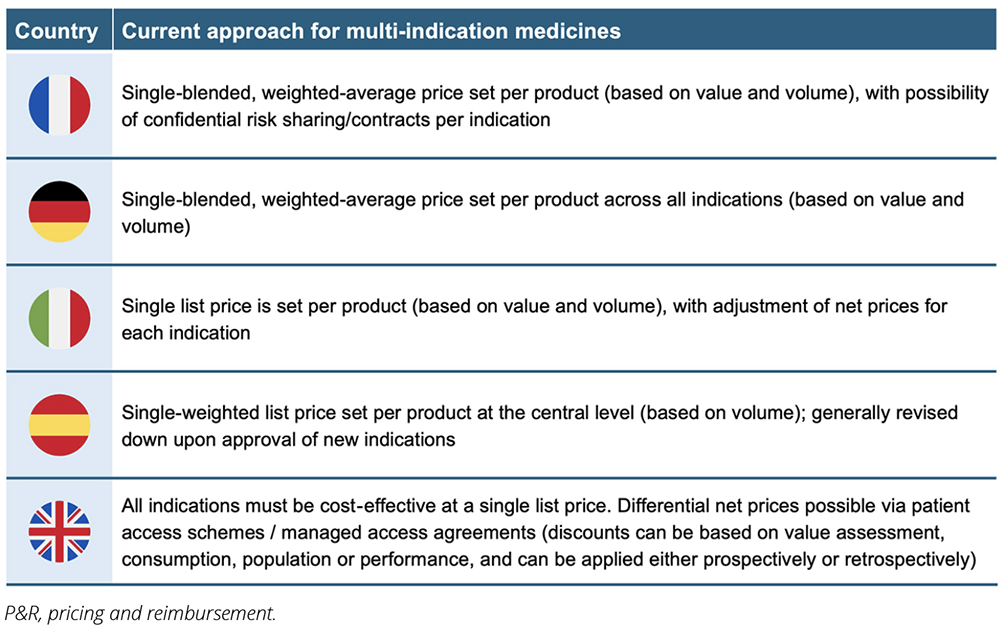

Current approaches to managing multi-indication medicines vary across European markets, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Approaches to multi-indication medicine P&R by European market.

While certain countries (eg, the United Kingdom, Switzerland) support differential discounting, where discounts to the list price are negotiated for each indication resulting in different net prices, the focus among major markets has generally been on blended (weighted-average) pricing.22-26

While some healthcare payers may view existing systems as fit for purpose,23,27 these indirect forms of IBP do not truly capture incremental value at the indication level.22,23,28 Rather than enabling both upward and downward price adjustments, these approaches are often associated with substantial price erosion upon indication and volume expansion, irrespective of the value of the new indication.12,23,28 Moreover, price negotiations are often lengthy in practice.22 This can result in launch sequencing, reduced R&D incentives to develop and launch new valuable indications, and suboptimal patient access to multi-indication medicines.12,23,24,28

An optimal theoretical solution for multi-indication medicines is “pure” IBP, as identified in the literature, discussed by ISPOR panelists and highlighted by Barros et al.12,15,28 IBP involves assigning distinct prices to each indication based on its clinical benefit, ensuring full alignment of price with value.24 In practice, this typically involves maintaining a single public list price while confidential net prices are negotiated separately for each indication.29 However, it has been highlighted that pure IBP may not be a feasible solution in practice, at least in the short-term. This is due to implementation barriers such as insufficient data infrastructure to track utilization by indication and lack of financial systems to support payment and financial reconciliation.12,23,24

Moreover, where IBP has been applied previously, there have been significant delays to access (eg, in Italy, negotiations lasted for 603 days for follow-on indications vs 583 days for initial indications).22

Proposed approaches for multi-indication medicines

Given the constraints of pure and indirect forms of IBP, the ISPOR panel and Barros et al stressed the opportunity to have pragmatic, short-term, alternative solutions for multi-indication medicine access and the need for these to be developed through multistakeholder collaboration.15,30

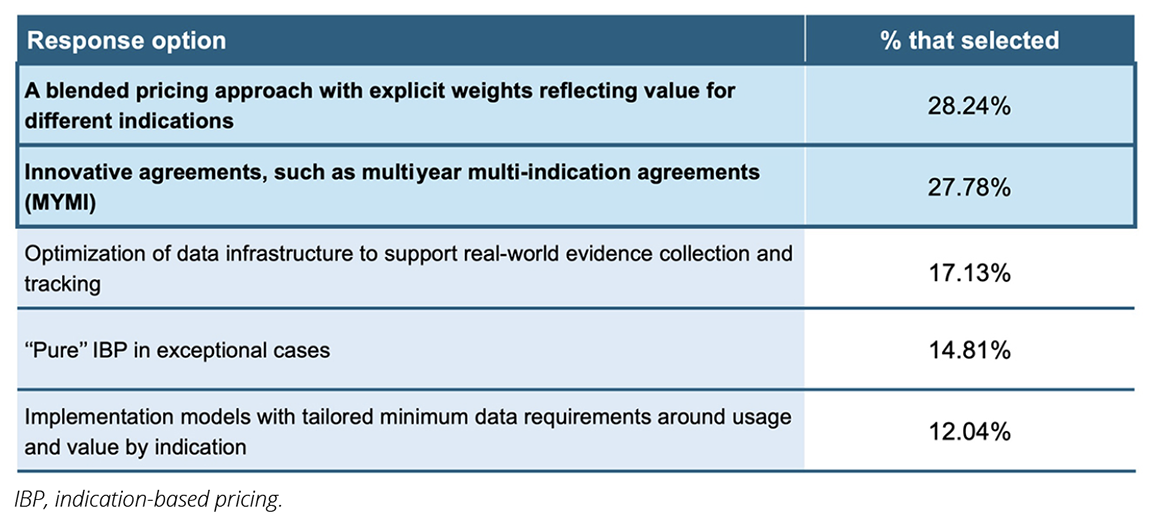

Through the ISPOR audience survey, participants ranked the following potential solutions as the most effective and feasible (see Table 2).30

Table 2. ISPOR panel audience results.

Of the 2 most-selected options, blended pricing approaches have been thoroughly discussed in the literature. While innovative agreements like multiyear multi-indication (MYMI) have been briefly highlighted in the literature as having high potential, with previous use in European countries (eg, Belgium, the Netherlands),14,31 further investigation is required to understand if they can offer additional benefits over existing approaches.

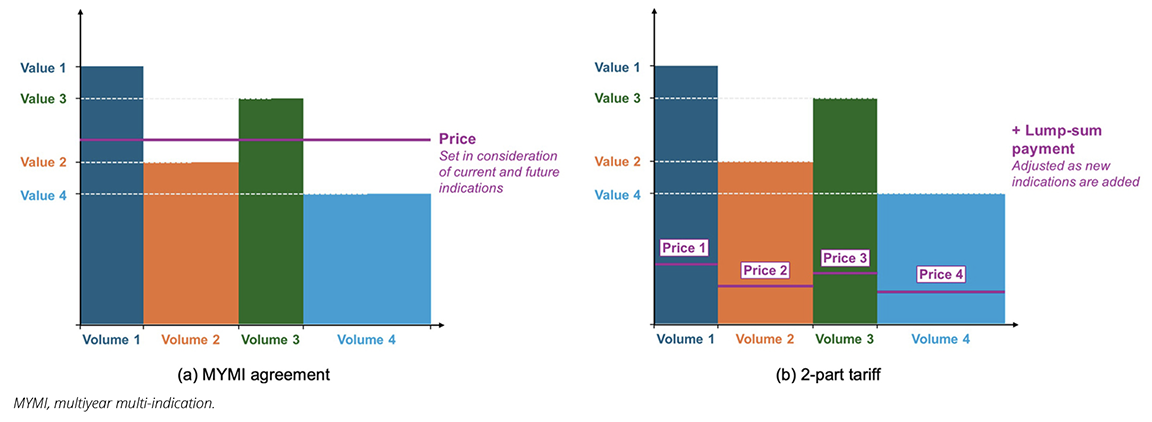

A MYMI agreement is a holistic agreement between manufacturers and payers across multiple indications and years, creating a comprehensive framework for value assessment and P&R for a product’s current and future indications.14,31 Instead of full upfront assessments and price negotiations for each new indication, MYMI involves a predefined arrangement with several different elements to enable access to all indications through streamlined value assessment processes, resulting in immediate or accelerated reimbursement of new indications where clinical value meets predefined criteria (see Figure 2a).14 In 2017, the first MYMI agreements were established in Belgium, in which all reimbursed PD-(L)1s would have new indications automatically reimbursed within 1 month of EMA approval. These agreements resulted in patient access being accelerated by over 550 days.31

MYMI agreements have been linked to several benefits for a range of stakeholders, including accelerating and broadening patient access to new indications, reducing submission and assessment workload, and improving budget/price predictablity.14,24,31 To ensure value is maintained, periodic re-evaluations and price adjustments can occur.14 Implementation of such agreements does not require tracking of utilization by indication, which would require sophisticated data infrastructure and is, as indicated before, difficult for often overlapping autoimmune conditions.

Multiyear multi-indication agreements are most useful when a medicine has already demonstrated major benefit for its initial indication with many additional indications launching over an extended period.

The theoretical foundation described by Barros et al aligns closely with elements of MYMI. The authors discuss an approach they term the 2-part tariff, which combines unit prices per indication with a lump-sum payment (see Figure 2b).15 The lump-sum payment is adjusted independently of how unit prices are set to ensure that total payments are proportional to the overall benefit delivered, which the authors suggest could achieve the same outcomes as IBP.15 The 2-part tariff approach establishes rules for reimbursement of subsequent indications upfront, and it is focused on maximizing clinical benefit across all indications,15 which aligns with the MYMI approach and goal of encouraging launch across the full set of a product’s indications. Additionally, the 2-part tariff allows the lump-sum component to adjust flexibly both upward and downward as new indications are introduced.15 This flexibility supports long-term sustainability and underscores the shared principles and benefits of MYMI agreements and 2-part tariffs.

Figure 2. Simplified illustration of a) MYMI agreements compared to b) Barros et al’s 2-part tariffs.

While MYMI agreements have benefits, they are not without limitations. Such agreements come with risk, as they are negotiated based on limited evidence for future indications, with uncertainty around the eventual label, added benefit, timelines, and treatment alternatives. Payers and manufacturers may therefore be reluctant to commit to such agreements. MYMI agreements are most useful when a medicine has already demonstrated major benefit for its initial indication with many additional indications launching over an extended period. The uncertainty associated with MYMI can be mitigated by setting minimum benefit thresholds for new indications, and ensuring mutual trust, transparency, and collaboration between payers and manufacturers.

There is still a need to better understand the benefits of MYMI agreements, and if and how they can be practically applied in different countries. Bringing together the empirical evidence gathered so far and Barros et al’s framework reveals key elements that could inform the design of an effective MYMI implementation blueprint to determine their potential for improving development and patient access to valuable multi-indication medicines in practice.

Conclusions and Implications

Scientific advances have identified shared biological pathways between distinct autoimmune diseases and have opened the possibility for innovative medicines that can treat multiple conditions in these underserved conditions. At the same time, multi-indication medicines continue to face access challenges, particularly in the field of immunology, due to the complex and often overlapping nature of these conditions. To ensure patients with underserved autoimmune diseases can fully benefit from multi-indication medicines, it is important that they are managed in a sustainable manner for all stakeholders. There is thus a need for novel approaches to support development, approval, and access of multi-indication medicines as practical and effective short-term alternatives to IBP.

One approach that stands out as a potentially promising solution is the MYMI agreement, which may benefit all stakeholders through broad and accelerated launches, reduced administrative burden, and improved financial predictability.

A next step to explore this potential further would be to determine if and how MYMI agreements could be practically implemented in different country contexts. This requires stakeholder collaboration to create understanding between different perspectives and find consensus on the best ways forward.

References

- Arango M-T, Shoenfeld Y, Cervera R, Anaya J-M. Infection and autoimmune diseases. In: Anaya J-M, Shoenfeld Y, Rojas-Villarraga A, Levy RA, Cervera R (eds). Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside [Internet]. Bogota, Colombia: El Rosario University Press; 2013.

- Understanding autoimmune diseases. NIH News in Health. Published June 2022. Accessed August 27, 2025. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2022/06/understanding-autoimmune-diseases

- Conrad N, Misra S, Verbakel JY, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: a population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet. 2023;401:1878-1890.

- Bieber K, Hundt JE, Yu X, et al. Autoimmune pre-disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2023;22:103236.

- Multifaceted autoimmunity: new challenges and new approaches. eBioMedicine. 2023;88:104474.

- Autoimmune diseases. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Updated March 20, 2025. Accessed September 4, 2025. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/autoimmune-diseases

- Dresser L, Wlodarski R, Rezania K, et al. Myasthenia gravis: epidemiology, pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2235.

- Song Y, Li J, Wu Y. Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:263.

- Download medicine data. European Medicines Agency. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/download-medicine-data

- Gjølberg TT, Mester S, Calamera G, et al. Targeting the neonatal Fc receptor in autoimmune diseases: pipeline and progress. BioDrugs. 2025;39:373-409.

- Gores M, Scott K. Success multiplied: launch excellence for multi-Indication assets. IQVIA. Published 2023. Accessed October 30, 2025.https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/library/white-papers/iqvia-launch-excellence-for-multi-indication-assets-02-23-forweb.pdf

- Michaeli DT, Mills M, Kanavos P. Value and price of multi-indication cancer drugs in the USA, Germany, France, England, Canada, Australia, and Scotland. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2022;20:757-768.

- Position paper on drug repurposing. European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Published March 2024. Accessed October 2, 2025. https://www.efpia.eu/media/2mlhtlac/position-paper-on-drug-repurposing.pdf

- Lawlor R, Wilsdon T, Darquennes E, et al. Accelerating patient access to oncology medicines with multiple indications in Europe. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2021;9:1964791.

- Barros PP, Righetti G, Sa L. Pricing mechanisms for multi-indication drugs. Published August 12, 2025. Accessed September 23, 2025. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5374679

- Griffiths A, Economides S, Favier G, Healy J, Dewan S. The pricing and market access landscape for multi-indication products: challenges and opportunities in Europe. KPMG. Published 2023. Accessed August 27, 2025. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmgsites/uk/pdf/2023/10/the-pricing-and-market-access-landscape-for-multi-indication-products.pdf

- Delgado A, Guddati AK. Clinical endpoints in oncology - a primer. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11:1121-1131.

- Gianordoli APE, Laguardia RVRB, Santos MCFS, et al. Prevalence of Sjögren’s syndrome according to 2016 ACR-EULAR classification criteria in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Adv Rheumatol. 2023;63:11.

- Cherney K. What to know about lupus and Sjögren disease. Healthline. Published November 22, 2023. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.healthline.com/health/lupus/lupus-and-sjogrens

- Marques J, Lobato M, Leiria Pinto P, et al. Asthma and COPD “overlap”: a treatable trait or common several treatable-traits? Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;52:148-159.

- Purna Singh A, Shahapur PR, Vadakedath S, et al. Research question, objectives, and endpoints in clinical and oncological research: a comprehensive review. Cureus. 2022;14:e29575.

- Rossini EE, Galeone C, Lucchetti C, et al. From indication-based pricing to blended approach: evidence on the price and reimbursement negotiation in Italy. Pharmacoecon Open. 2024;8:251-261.

- Mills M, Kanavos P. Healthcare payer perspectives on the assessment and pricing of oncology multi-indication products: evidence from nine OECD countries. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7:553-565.

- Preckler V, Espín J. The role of indication-based pricing in future pricing and reimbursement policies: a systematic review. Value Health. 2022;25:666-675.

- Jung SM, Kim W-U. Targeted immunotherapy for autoimmune disease. Immune Netw. 2022;22.

- Campillo-Artero C, Puig-Junoy J, Segú-Tolsa JL, et al. Price models for multi-indication drugs: a systematic review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18:47-56.

- Cole A, Neri M, Cookson G. Payment models for multi-indication therapies. OHE. Published November 1, 2021. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.ohe.org/publications/payment-models-multi-indication-therapies/

- Mills M, Michaeli D, Miracolo A, et al. Launch sequencing of pharmaceuticals with multiple therapeutic indications: evidence from seven countries. BMC Health Services Research. 2023;23:150.

- Pani LC, De Luca A, Mennini FS, et al. Pricing for multi indication medicines: a discussion with Italian experts. Pharmadvances. 2022;4:163-170.

- Pricing and reimbursement of multiple indication medicines: Can a balance be found between different stakeholder perspectives to optimise value and access for patients, while ensuring sustainable and affordable innovation? Reported at: ISPOR Europe; November 17-20, 2024; Barcelona, Spain.

- Armstrong H, Petrova A, Wilsdon T, et al. Multi-year multi-indication agreements for supporting patient access to oncology medicines with multiple indications: an experimental approach or here to stay? J Mark Access Health Policy. 2025;13:2.