Distribution Markups and Taxes for Prescription Pharmaceuticals: Do We See the Complete Picture of the Pharmaceutical Price?

Giovanny Leon, MSc, MBA, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland; Panos Kanavos, PhD, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, England, United Kingdom; Christophe Carbonel, MD, MBA, Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland; András Inotai, PhD, Zoltán Kaló, PhD, Semmelweis University/Syreon Research Institute, Budapest, Hungary

Introduction

An analysis presented at the ISPOR Europe 2021 conference highlighted considerable variability across countries in how much pharmaceutical markups and taxes contributed to the total cost of pharmaceuticals. From a sample of 35 countries and across 3 selected Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) categories (including A10S, L1G, and N3A), pharmaceutical markups and taxes contributed $8.6 billion (22.3%) and $2.4 billion (6.2%), respectively, to the $38.5 billion total expenditure in 2020. In 14% of the countries, markups and taxes had an even higher contribution to the total cost of pharmaceuticals beyond ex-factory level. If the average 22.3% markup had been applied across all countries, a $2.4 billion saving could have been generated for third-party healthcare payers and patients.

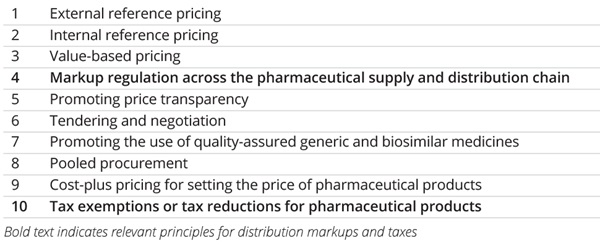

The World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies1 contains 10 principles for setting, managing, and influencing the prices of pharmaceutical products (Table). Despite their significant impact on total pharmaceutical spending, 2 principles, notably (1) markup regulation across the pharmaceutical supply and distribution chain and (2) tax exemptions or tax reduction for (prescription) pharmaceutical products, are often neglected in research, policy debate, and public forum discussions.

“Across countries, there are significant differences in the market entry and ownership criteria of retail pharmacies often grounded in history or geography.”

The WHO guideline outlines the objectives of national pharmaceutical policies, emphasizing patient access, quality assurance, and rational pharmaceutical use, all of which necessitate a well-functioning pharmaceutical supply system.

The variability in markups and taxes indicates that the global health economics and outcomes research community needs to address the full spectrum of pharmaceutical price regulation and explore the impact of the additional price components and taxes on the final cost that health systems (or patients if health insurance coverage is incomplete or inadequate) will incur.

Table. World Health Organization’s principles for setting, managing, and influencing prices of pharmaceutical products

Retail Pharmacy Sector

Across countries, there are significant differences in the market entry and ownership criteria of retail pharmacies often grounded in history or geography. Additionally, there is a diverse range of markup practices and, consequently, the operational cost of distribution is different, partly based on retail pharmacies’ local roles and responsibilities. Over time, there has been a transition to regressive markups and, in some cases, flat fees. In some countries, the retail pharmacy sector has undergone consolidation aiming at increasing efficiency gains for the system under the assumption that horizontal integration could reduce retail distribution markups.2 The efficiency gains from this consolidation do not appear to have been translated into health system or patient savings. Still, the optimal proportion of pharmacy markups (compared to the ex-factory price) and the policy implications of different markup approaches remain debated areas.

Variable distribution markups for different types of pharmaceutical products may be a reasonable approach: for cheaper products, regressive markups could be appropriate; for higher-priced specialty products, flat fees and potentially alternative distribution models could be more suitable, such as the exclusion of traditional retail pharmacies or wholesalers (ie, direct-to-pharmacy ) from the distribution system, especially if special transport or delivery is required. Additionally, certain financial incentives should be considered for pharmacies when implementing specific policies. For example, generic substitution could be incentivized through flat markup or dispensing fees for pharmaceuticals with the same active ingredient; equally, additional service fees could be implemented for pharmaceutical care or adherence-enhancing interventions, especially in countries with shortages in primary care professionals.

“Certain financial incentives should be considered for pharmacies when implementing specific policies.”

Lower-income countries (LICs) usually place less emphasis on controlling pharmacy markups compared to controlling ex-factory prices. Net pharmacy markups may be proportionally higher in LICs than in higher-income countries due to, first, the political and economic imperatives of remunerating domestic retail pharmacies and, second, the widely used confidential price reductions, clawbacks, or payback mechanisms, that are implemented to improve patient access to pharmaceuticals without compromising healthcare system financial sustainability.

Pharmaceutical Wholesaling

In pharmaceutical wholesaling, the public service obligation implies keeping a broad portfolio of pharmaceuticals for common diseases in stock by the largest possible number of traditional full-line wholesalers. However, the emergence of new distribution models, such as the direct-to-pharmacy model, the reduced wholesaler model, or the agency model (ie, where wholesalers become logistics providers on behalf of manufacturers) with a significant home care component, could be observed that may be more suitable for prescription pharmaceuticals requiring special distribution (eg, cold chain).3

Pharmaceutical wholesaling has undergone a significant degree of consolidation in recent years. Horizontal integration may yield modest efficiency gains and, amongst wholesale and retail distribution outlets, may contribute to more significant efficiency gains, resulting in a potential decline in distribution costs. While vertical integration may generate significant efficiency gains, it may also stumble across national regulation, limiting (or altogether forbidding) this from taking place.

There are political incentives to reduce wholesaler markups and discourage vertical integration in those LICs where large wholesalers are international companies rather than domestically owned ones. However, it is also crucial to recognize that meager distribution costs or geographical challenges (eg, large distances) may affect pharmaceutical quality and supply reliability, especially in some LICs.

Overall, in both wholesaling and retailing, there is considerable need to reset policy objectives and implement change, such as monitoring public prices (rather than ex-factory prices only), pharmaceutical utilization, and proposing changes in markup regulations that reflect the changing market dynamics and the changing nature of newly launched pharmaceutical products. Balancing policy objectives by considering the quality of pharmaceutical provision, incentives in the supply chain, healthcare financial sustainability, and the prevention of catastrophic out-of-pocket spending would be essential in this context.

Taxes and Custom Duties

From a fiscal policy perspective, prescription pharmaceuticals are considered a commodity with specific regulations on consumption taxes, such as value-added tax (VAT), as well as the imposition of import or customs duties.

There is a heterogeneous picture of VAT rates for prescription pharmaceuticals across countries. The macro-level fiscal balance must be considered to determine the impact of taxation on affordability both from health system and patient perspectives, the latter if patients face a significant out-of-pocket burden. In a publicly funded healthcare system, imposing VAT on prescription pharmaceuticals amounts to a stealth tax, depriving health systems from valuable resources by returning these to national treasuries. Upon recognizing this, several countries have implemented reduced or zero-rated VAT on prescription pharmaceuticals. National and international policy organizations recognize the importance of exempting essential health goods (such as prescription pharmaceuticals) and services from VAT and safeguarding equity. This is critical for individual consumers or patients because indirect taxes, such as VAT, are regressive; where patients face significant out-of-pocket costs from prescription pharmaceuticals, VAT may contribute to patients not being able to fill prescriptions, thereby increasing inequity in access. For a variety of reasons, LICs prefer to raise revenue from indirect (rather than direct) taxation; while this is understandable, based on their revenue-raising capacity, it is not particularly helpful if indirect taxes are imposed in the same blunt manner on prescription pharmaceuticals.

“Lowering or altogether eliminating customs duties would improve patient access to essential pharmaceuticals.”

The magnitude of import or customs duties also carries important policy implications, especially in those LICs where most higher priced prescription pharmaceuticals are imported. Lowering or altogether eliminating customs duties would improve patient access to essential pharmaceuticals. This is supported by the European Union’s (EU) zero customs duties policy for EU products. Many LICs impose customs duties on finished products to disincentivize their importation, due to favoring import substitution and increasing local content and local manufacturing; this is typically done by subjecting imported active ingredients to zero customs duties. Local manufacturing activity, typically centering on multisource products, continues to drive the need for higher customs duties on imported originator or off-patent branded pharmaceuticals. Again, a balance is needed to ensure that essential pharmaceuticals that cannot be manufactured locally are not subjected to unnecessarily high customs duties that ultimately endanger patient access.

Overall, taxation and customs duty policies should aim to improve rather than discourage patient access and affordability without jeopardizing macrolevel fiscal balance. To that end, alternative sources for tax revenue could be pursued instead of prescription pharmaceuticals.

Conclusion

Policy debate on fair pharmaceutical prices focuses intensely on ex-factory prices. However, the actual impact on the healthcare system is much higher due to distribution markups and taxation. Besides providing sufficient remuneration for a quality distribution system, markups should be related to the workload and provide incentives for pharmacists in implementing policies (eg, generic substitution, adherence-enhancing interventions). At the same time, due consideration should be given to reducing or eliminating taxes and/or customs duties on prescription pharmaceuticals.

While most EU member states have a detailed regulatory framework for distribution markups, several LICs may lack such mechanisms. It is suboptimal if pharmaceutical distribution markup structures and taxation practices are only based on historical principles or purely fiscal imperatives. There must be consensus on principles and objectives in each setting guided by fairness and equity in patient access, the contribution made by different actors in the pharmaceutical value chain, and an understanding of how regulation reform (including pricing regulation) can lead to optimized performance of distribution practices.

This article is also a call for action on routine data collection and analysis on pharmaceutical cost elements and on facilitating evidence generation on the impact of distribution markup and tax regulation in both higher- and lower-income countries to increase awareness and explore improvements in pharmaceutical care macro-level efficiency.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies, second edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2020. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240011878

2 Kanavos P, Schurer W, Vogler S. The pharmaceutical distribution chain in the European Union: structure and impact on pharmaceutical prices. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2011. Published March 2011. Accessed July 7, 2022. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/51051/1/Kanavos_pharmaceutical_distribution_chain_2007.pdf

3 Kanavos P, Wouters O. Competition issues in the distribution of pharmaceuticals. DAF/COMP/GF(2014)8. OECD; 2014. Published February 3, 2014. Accessed July 7, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF(2014)8&docLanguage=En